Discussions on curatorial projects, museum collections, classification and categorization of museum objects and institutional histories across the globe have gathered much public attention crossing the scope of academia through zoom webinars during this pandemic era. Scholastic repositories are gradually opening up, and research-driven methodologies are being imbibed more in artistic dialogues of our time, touching upon the range of data that scholars and historians once exclusively determined. In this scenario, I often find myself submerged in the ocean of historical data only to peep out to comprehend the cultural precipice being built on the disciplinary field of art practice and its history. How much have we negotiated with the classifications in a material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices? Sifting through these questions can also reveal the awkwardness in institutional conservatism that has been set in loop. There are no right or wrong conclusions to these inquests, but a historical trail can lead us to the beginning of the hallowed domain of making the ‘modern and contemporary art’ genre in India, which is vehemently addressed as institutional agendas. And the domain of ‘Exhibition Making’ in the country has been the prime vehicle of the genre.

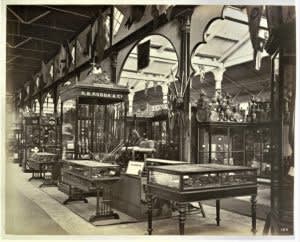

General view of the Calcutta International Exhibition, demonstrating the vast scale and display courts. The white building on the extreme right is the Indian Museum, bridged with the other courts on Maidan. 1883-84

I will discuss many critical facets of this argument through a series of blog posts, and I shall begin with a discussion on – The Calcutta International Exhibition, the first grand exposition in the Bengal Presidency. The Exhibition took place from 4th of December 1883 to 10th of March 1884. Jules François de Sales Joubert, an entrepreneur, French by birth but later having migrated to Australia, initiated and organized the Exhibition after the tremendous success at Exposition Universelle of 1878 and the 1881 Perth Exhibition. Countries represented at the Calcutta International Exhibition were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, the United States of America, Japan, Switzerland, Spain and many more, along with all the British colonies and all Indian provinces. This was claimed to be India’s own Great Exhibition (The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, Crystal Palace UK), but a more home-grown edition of an international exhibition of a complex scale (Peter Hoffenberg, 2003). This historical Exhibition is also very vital as it was the first time the people of Calcutta witnessed the conglomeration of nations from across the globe in the city, with their inventory of industrial examples, raw products, food products, agricultural goods, specimens of ethnography, archaeology and natural history, objects of personal use like toiletries, apparels etc., along with fine arts and liberal art examples. It has been noted in the Official Report of the Calcutta International Exhibition that “(it) was the first attempt made in India to hold an exhibition of international character. Exhibitions on a smaller scale had been held in various parts of India, but these were generally of a local character; and where their scope was purely provincial, no attempts were made to include in them specimens of other than Indian arts and manufactures. For the improvement of Indian art, these exhibitions were not without considerable value, but they necessarily did not embrace the other important objects of an exhibition – the bringing of distant countries into closer commercial union with India and the development of new branches in the industry. This could only be done by means of an exhibition on a much larger scale than any previously attempted in India.”

The driving intention was to open up the market in India for larger exchange in functional and cultural goods with the objectives of cross-cultural orientation. On a broader scale, the Exhibition also educated the design of the display, thrusts of collection direction and the tools of cross-cultural knowledge accumulation in India. The objective of any exhibition is tied to three interests – display of authority over a subject, establishing the trends of the time and ensuring development in the field. The Calcutta International Exhibition had brought together the vision of regional, national and international within the experience of the colonial display. However, countering the ambition, the Exhibition failed to garner neither scholarly nor mainstream commercial interests in comparison to the cultural success of the Great Exhibition of 1851. ‘World Fair’ events were one of the primary methods of the British monarchy that would facilitate the accumulation of resources and cultural specimens from all its colonies. The question is - why is the Calcutta International Exhibition remembered as British India’s first and also the last international fair?

Renate Dohmen clarifies in her essay, disputing Hoffenberg and the British India government’s claim of triumph, that how this Exhibition failed to mark Calcutta as the ‘new’ metropolis of staging international exhibitions. Two crucial observations can be noted for this failure – first, a more bureaucratic reason was the rising animosity between Indians and Europeans due to the Ilbert Bill. This acrimony resulted in the marked absence of Europeans, whether residents or travellers, from the Exhibition. The second factor of failure was in the lack of analysing the difference in trade impetus between the colonizer and the colonized. Recreating and marketing the exotic-ness of a distant land like India in the West has been the core of commercial and cultural success post-industrial revolution for the colonizers. However, not every aspect of the Exhibition resulted in a quagmire. By the 1880s, the Indian Museum claimed and functioned from its current location and the zoological and archaeological section was transferred to the museum building, and the galleries were open to the public. In the Centenary volume of the Indian Museum, it is noted that in 1882, the Government of India enquired whether accommodation could be provided in the museum to make space for economic products. “The Trustees regretted their inability to accommodate such a collection but expressed their readiness to favour an extension of the museum building for the purpose suggested”. But before this proposal was taken to effect, the Calcutta International Exhibition was held in and around the museum premise. In this context, the Official Exhibition Report from the Australian colony of Victoria records, “Over 300 applications for space were received, the number of separate exhibits amounting in aggregate to 2,346, a number considerably in excess of that forwarded to any previous exhibition outside the colony.” The official report holds a very descriptive account of the layout of the exhibition space to the distribution of galleries to the categorized display of the objects. It shows that the main entrance to the Exhibition was through a wooden foot-bridge over the Chowringhee road into the museum, opening up to the portico of the museum. The physical involvement of the Indian Museum allowed linking itself to a more inclusive method of collection and display. The institution became an indispensable part in executing an international exhibition of an ambitious scale and contributed to the public (democratic) discourse of display and gaze.

But the capacity of the museum was not limited to being a centrepiece venue of the Exhibition but of a more active facilitator in the post exhibition scenario. In 1884, after the Calcutta International Exhibition had been concluded, the Industrial collection which had been brought to the museum for the exhibition purpose, under the designation of Bengal Economic Museum had been housed in temporary sheds on the site that was later (and currently) occupied by Calcutta School of Art (now Govt. College of Art & Craft, Calcutta) was amalgamated with the Indian Museum. The Calcutta School of Art moved to the Chowringhee premise from 163 & 164 Bowbazar Street, in 1893 and the Government Art Gallery travelled the same distance, with all its collection in 1895. It is quite thought-provoking to observe how the formation of space identity and exhibition memory established the precedence for Govt. College of Art & Craft and was naturally imagined in liaison with the Indian Museum.

The scale and scope of this exhibition was colossal - eleven sections were divided under every key province of India and foreign countries represented in the Exhibition. But we will for now, stick to the Calcutta scene. Section one was ‘Fine Arts’ that listed paintings and drawings, sculptures, architectural drawings and models, engravings, lithographs, photography and ‘works of art not specified’ all sourced from manufacturers, printers and private collectors. Contradictorily and therefore curiously, the J J Art School was categorized under the Bombay Court of ‘Education and Application of Liberal Arts’; but similar consistency was not observed in the case of the Calcutta Art School. The works by the student of the school were listed under the ‘Education and Application of Liberal Arts’ of the ‘Indian Court’. The official report of the exhibition records that students of the Calcutta school of art displayed a considerable variety of artworks, which satisfactorily demonstrates the range and depth of art education in the city. Some of the works on display were – watercolour portraits by Mahendranath Chaudhuri, Nabakumar Viswas, Jadubkrishna Bhattacharjee, Harinarayan Basu, Krishna Chandra Pal, Barada Kanta Dutta; Life study in Oil by Narayan Das Mitra, Digbijoy Neogi, and Nrityakali Mukherjee and many more.

One might fairly question the relevance of digging up this history of exhibition and the colonial bureaucratic scheme that was at play in 2021. To them, I say, that it is important to remember these artists, whose artistic credibility and participation have been seldom recognized within the larger scheme of institutional narratives and art historical writing. None of these works or any pictorial documentation of these works exists. As much of Indian (modern) art history has been written through the interdependence of object + character +style + spectacle tropes, without critiquing classifications and the positions of lesser prominent artists within the entire system, the gap in the politics of representation has grown its roots. Using pedagogy as a dogmatic tool, colonialism has conditioned our viewing methods for the past hundred years. Perhaps we can position certain questions as prompted at the beginning of this essay through our own intellectual practices?

References

-

Peter Hoffenberg, “Photography and Architecture at the Calcutta International Exhibition, 1883-84,” in Traces of India: Photography, Architecture, and the Politics of Representation, 1850-1900 (Montreal, 2003).

-

Renate Dohmen, “A Fraught Challenge to the Status Quo: The 1883-84 Calcutta International Exhibition Conceptions of Art & Industry and the politics of World Fairs”, 2016. P200-205

-

Official Report of the Calcutta International Exhibition, 1883-84 Vol I & II. Compiled under the orders of the General Committee, Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta, 1885

-

Official Catalogue of the Calcutta International Exhibition, 1883-84. Third Edition. Printed and published under Special Authority by W. Newman & Co. Dalhousie Square, Calcutta.

-

The Indian Museum 1814 - 1914. Published by the Trustees of the Indian Museum. Printed at the Baptist Mission Press. 1914 Calcutta

[All photographs taken by Mr. A. W. Turner, under the direction of the Government of Bengal. Printed and Published by the Survey of India Dept., Calcutta 1884]

Sampurna Chakraborty is an art historian, researcher and writer, working on Institutional History, Art Pedagogy, Archival Methodologies, Spectator Participant Methodology, and Participatory Curatorial Cultures. Her exhibition reviews, articles and research essays are published in art magazines and peer-reviewed journals in India. She is an alumna of Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, and she is currently pursuing her PhD research from the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.