The first essay in this series (https://www.emamiart.com/blog/mapping-the-field-of-exhibition-history-the-calcutta-international-exhibition-of-1883-84/) discussed the workings of ‘world exhibition’ culture that was introduced in Calcutta, through the Calcutta International Exhibition in 1883-84. This exhibition remains to be the first and the last exhibition of a monumental international scale of the pre-independent India, as the exhibition format and its objectives which adhered largely to colonial thrusts of trade policies, didn’t find lasting grounds in Bengal. This failure was due to the rising animosity between the Indians and European population in Bengal stirred by the Ilbert Bill (1884) and also due to the lack of scholarly and commercial interest in the fair. However, the consequences of the large-scale circulation of art objects and artifacts during the exhibition made a significant impact on the colonial art education policy and on the rearrangement of object categories in the Indian Museum – a detailed account of which has been shared in the previous essay. As this series of episodic essays intend to raise some fundamental questions like – “How much have we negotiated with the classifications of material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices?” Through the trope of the exhibition as a facilitator, each blog post will trace and analyze the foundational methodologies of exhibition-making as a modernization process in the region; and the current second essay will look into the formation of the first public art gallery in Calcutta.

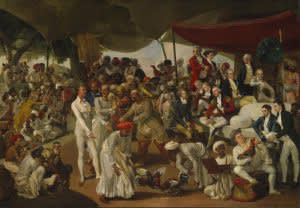

Much before the establishment of the art school in Calcutta in 1854, or as it was then called ‘The School of Industrial Art’, Calcutta witnessed its first ‘fine arts’ exhibition in 1831 by a group of British artists. They formed a collective called the ‘Brush Club’, and it consisted of British artists who were residing in the city, as well as British artists who were visiting. These exhibitions essentially consisted of European styles of portrait and landscape painting by William Hodges, Tilly Kettle, George Chinnery, John Zoffany and their likes, along with English Royal Academicians like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Sir Henry Bourne, Benjamin West etc., firmly establishing the scope of ‘fine arts’ status to Western naturalism. Though the list of artists, artworks, and members of the group was strictly Eurocentric, gradually over the years, names of wealthy Bengali donors and patrons started appearing in the exhibitions catalogs. And the corpus of Eurocentric art circulated within Bengal, as well as in other provinces of India, became to be culturally conditioned as the genre of ‘Fine Arts’.

During the next two decades, the city of Calcutta witnessed an urge to create exclusive spaces of viewing in galleries and private clubs for ‘Art’, more accurately Western Art, as the domineering narrative for art appreciation in the city. And the Government School of Art, Calcutta, was still negotiating its pedagogic direction between the propagation of craft culture of the region, decorative commission works, and western academic art modules.

Owing to the desired progress of the Government School of Art, towards dexterity in industrial arts as well as in naturalistic style of portrait painting, as demonstrated through multiple commission projects and annual art exhibitions organized by the institution, the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, with the support of the Viceroy Lord Richard Northbrook established the first dedicated art gallery in the city housed in No.164 and No. 165 Bowbazar Street in 1875, interconnected with the Government School of Art, which was then housed in No. 166 of the same street. Viceroy Lord Northbrook visited the art school on May 18, 1872, for the first time to see an exhibition of the art student’s works. He later commented, “in respect to wood engraving, lithography, painting, and drawing, executed in that school which would, I do not hesitate to say be a credit to any institution of the same class in any part of England.” Since then, Richard Temple, the then Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, took a keen interest in the art institution and, with Lord Northbrook’s contribution, established the art gallery in the art school. Richard Temple further augmented the pedagogic significance of the initiative.

In such a place as Calcutta the establishment of an art gallery must be interesting from any and every point. But the interest is heightened when the gallery can be the means of daily instruction; will become a lecture-room for classes of native students; may impart additional vigour to an institution designed to elevate the taste, refine the skill and enlighten the ideas of the native youth who are learning art as the means of livelihood; and may thus serve an important educational purpose. (Richard Temple, 1876)

Establishing a central pedagogic trajectory of the art gallery collection with that of the Government School of Art, Calcutta, the scope of the art education in this institution specifically had begun shifting from industrial and craft centric modules to an apparently elite position of ‘fine arts’. The art gallery was built on a collection of artworks that were gifted by Lord Northbrook, comprising of European examples of art, few original and largely copies, to strengthen and further refine the academic aspirations of the art students and synthesize the ideals of western taste and aesthetics among the native population. This collection included paintings like the Marriage of the Virgin attributed to Rubens, Saint Cecilia after Domenichino, Interior of a Church by School of Steinwick, a copy of Joshua Reynold’s Infant Hercules Strangling Serpents and Lord Clive and His Family, a portrait after Velasquez by R. Muller and many other vital examples of Western art. His gift to the art gallery also included a valuable portfolio containing thirty-eight engravings of the frescoes of Giotto, fifty-eight chromolithographs, and twenty-eight engravings of the Arundel Society, a portfolio of twenty-nine watercolor drawings of the Taj Mahal and other specimens of etching and engraving. The art gallery also collected “plans and drawings of great engineering work in all parts of the world” to provide a stronger foundation for the professional aptitude of the art students (Temple, 1876). This large and rich pool of European art at the Government School of Art, Calcutta, provided an intense western orientation of artistic aspiration for the art students of the institution. Much before E.B. Havell displaced this collection of European art with that of Indian examples (like miniature and manuscript paintings and varied forms of indigenous decorative art now in the Indian Museum) and officially established the ‘fine arts’ division of the institution in 1897-98, the ambit of fine arts had already been established for the Government School of Art, Calcutta, through the formation of the art gallery.

According to Richard Temple, the art gallery space Bowbazar was “being rapidly prepared by the Public Works Dept. for the reception of pictures” (Temple, 1876), acknowledging H. H. Locke’s repeated insistence to the government since the early 1870s to expand the logistical infrastructure of the school building, so that the institution can flourish and lead the cultural milieu of the region. Temple notes that the rest of the art gallery collection had been built with investments for this purpose by the Govt. of Bengal; and “many also have been promised to be lent for a temporary exhibition in the gallery by the native chiefs and gentlemen, among whom may be mentioned the Maharaja of Burdwan, Raja Jotendro Mohun Tagore, Raja Hunendra Krishna, Raja Satyanund Ghosaul, the Zamindar of Paikpara and others; also copies are being made from private pictures now in Calcutta; one picture too has been presented by Mr. Palmer” (Temple, 1876). Temple also pointed out that the government was interested in collecting, “a vivid and comprehensive representation of all that is most instructive and attractive in the extraordinary varied features of India, chiefly as regards to natural scenery, architecture remains, national costume and ethnological features”, completely disregarding Indian artistic traditions and its history. The government of Bengal had also ordered copies of works from old masters by Signor Pompignoli of Florence and purchased Colonel Hyde’s collection of electrotypes from ancient Greek coins, which were in possession of the British Museum. Locke was designated to be the keeper of the gallery, and the government sanctioned an annual grant of ten thousand rupees for the purpose of art collection.

J.C. Bagal later noted that there were twofold objectives towards establishing the Government Art Gallery, “The object of the institution was to give the native youth of India an idea of men and things in Europe both present and past, not that they might learn to produce feeble imitations of European art, but rather that they might study European methods of imitation and apply them to the representation of natural scenery, architectural monuments, ethnical varieties and national costumes, in their own country” (Bagal, 1966) . The canons of western aesthetics, which continued to inseminate the cultural and artistic psyche of India for decades, had shaped the fundamental pedagogic distinctions in academic Indian art practices. The nomenclatures like ‘still-life’, ‘life study’, ‘light and shade’, ‘realism’, ‘naturalism’, ‘picturesque’ etc., entered the idiom of art and pedagogy in India, and we find examples of such nature in the class works of art students. The colonial tendency toward academic art training was demonstrated through generations of artists who entered an unaccustomed structure of cultural classification that was abruptly implanted through the pedagogic project. Notwithstanding the parochial pedagogic direction of the school, the establishment of the art gallery as an institutional, cultural and pedagogic bridge with the museum provided a strong impetus for the reorganization and segregation of ‘fine arts’, ‘industrial arts’ ‘economic products’ and ‘decorative objects’ in the nineteenth century Bengal. Indian Museum, which until the early twentieth century dealt essentially with the Zoological, Botanical, Ethnological, Industrial and Archaeological collection, gradually expanded its scope to cultural edifices and artistic traditions of the country in connection with the Government Art School. What we know of the art collection in the Indian museum today significantly forms the nucleus of modernism in Indian art and its history and the core of Bengal’s artistic identities. The configuration of this art collection was essentially a reflection of art pedagogic developments which were unfolding at the Government School of Art, Calcutta; and the displacement of artistic lineage from colonialism to nationalism, through the device of exhibition practices, within the site of an institution. The practice of art collection and ‘exhibiting’ became interwoven aspirations for art students and artists in India with the along with the process of art-making.

Reference

-

Public Instruction in Bengal – Annual Reports 1871-76, The Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta

-

Meeting Minutes of the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, dated Feb 15, 1876. On the subject of “Establishment of an Art Gallery in connection with the School of Art at Calcutta” (West Bengal State Archive)

-

Tapati Guha-Thakurta. The Making of a New Indian Art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal c1850-1920, Cambridge University Press, England, 1992

-

C. Bagal. History of the Government College of Art & Craft, Calcutta, 1966

Sampurna Chakraborty is an art historian, researcher and writer, working on Institutional History, Art Pedagogy, Archival Methodologies, Spectator Participant Methodology, and Participatory Curatorial Cultures. Her exhibition reviews, articles and research essays are published in art magazines and peer-reviewed journals in India. She is an alumna of Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, and she is currently pursuing her PhD research from the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.