The Kalighat Patuas, named so since they mainly settled in and around the Kalighat and Tarakeshwar Temples in Calcutta, migrated from various parts of Bengal, especially regions of Birbhum, Murshidabad, and Medinipur, the erstwhile royal centres. History shows that no cultural or intellectual output can exist in a vacuum. The contemporary emergent issues and pressing anxieties plaguing the milieu of Calcutta eventually tended to find their way into the Patachitras. As the work of Tapati Guha-Thakurta has shown, the emergent ideas of colonial modernity, a middle class with the hope of embourgeoisement and the pressure of anti-colonial nationalism resulted in the adoption of secular events, which became widely popular in colonial Bengal. This led to a distinct style of new Bengali modern art that grew into a mass visual culture. It is important to note that in such a situation of intense anxiety, the new Bengali middle classes invested all their hopes in increasingly revivalist rhetoric. This, among its other manifestations, included an increasing importance of women as the repository of a nascent nation and a fetishization of their sexuality and purity. Interestingly, such representations of the feminine found their way into the Patachitras but in different ways. The recurrent themes were that of the ideal housewife or the Grihalakshmi, of the new woman- the Western Educated modern female, and of the ridiculed woman depicted as driven by lust and visualised as someone capable of torturing the opposite gender and her in-laws.

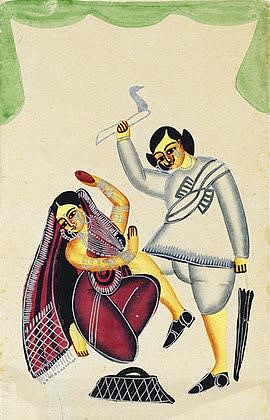

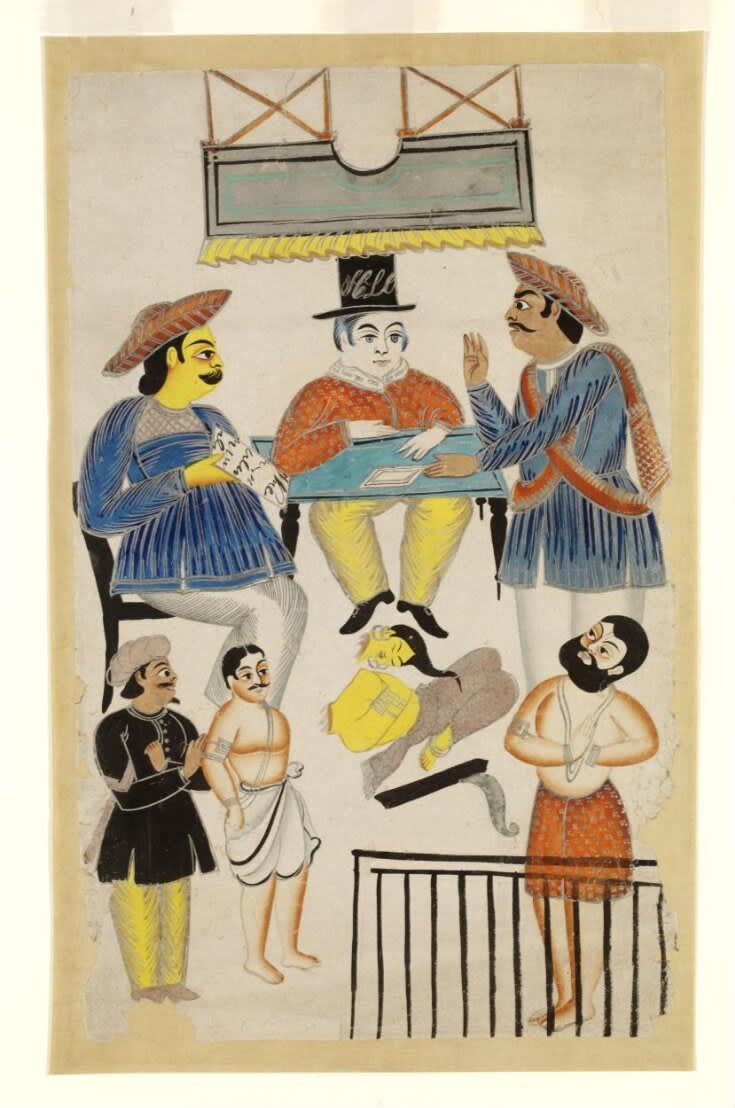

Scene of the trial of Mahanta, Elokeshi’s body in court | Watercolour on paper | V & A Museum Collections

An interesting case study in this context could be the Elokashi pictures: a series of Kalighat paintings depicting a case that rocked the Bhadralok milieu. It resulted from a supposedly illicit love affair between Elokeshi, the wife of government employee Nobin Chandra, and the Brahmin head priest (or mahant) of the Tarakeshwar Shiva temple. Nobin subsequently decapitated his wife, Elokeshi, in a fit of anger. A highly publicised trial followed, dubbed the Tarakeswar murder case of 1873, in which both the husband and the mahant were found guilty to varying degrees, including the intoxication of Elokeshi by the mahant. Bengali society considered Mahant’s actions as punishable and criminal while justifying Nobin's action of killing an unchaste wife. The resulting public outrage forced authorities to release Nobin after two years.

Catering primarily to the subaltern working-class residents of the city, these pictures express a consciousness that was very different from that of the middle class. The Patachitras depicted folk morality, bringing symbolic justice to Elokeshi with an unprecedented form of strength. The picture depicts the woman’s corpse in a courtroom full of men where Elokeshi, a woman from a conservative rural household, could finally become a part of the public sphere. This points us to how art and its depictions often pave the way for showing the socio-economic developments of the society and the anxieties as well as aspirations of the people it represents. The Kalighat style of paintings also boasts many great stalwarts in the post-independence era. Gradually, this school adopted the themes to match the “High Art” standard and shed its subaltern touch, increasing its take on non-contemporary themes.

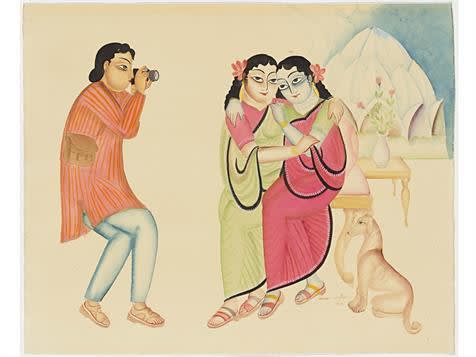

A same-sex couple in front of Lotus Temple | painted by Kalam Patua | Watercolour on paper | Google Arts and Culture

A welcome break to this pattern can be seen in the work of Kalam Patua, a self-taught contemporary exponent of Kalighat paintings. He works as a postmaster in Rampurhaat, Bengal and also invests his time in keeping the tradition of painting Patachitras alive. In his work, we see the depiction of the feminine in a very different manner. No longer is she the ideal housewife or mother, nor an evil corrupted woman out there to destroy all traditional values and sensibilities. Kalam’s female protagonists are contemporary women owning their voices and agency. I want to highlight here two works of the artist to portray this point.

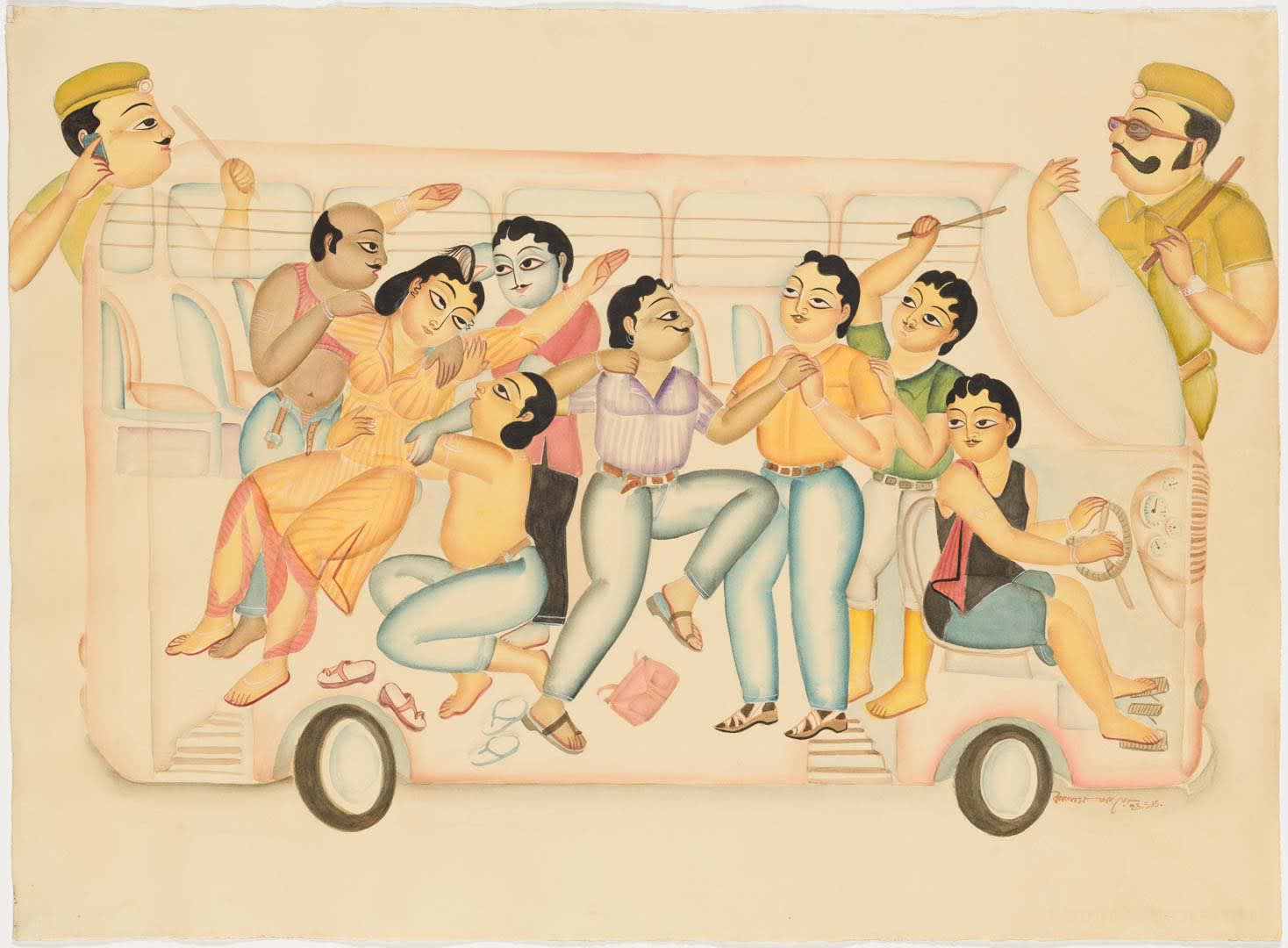

First is the image of a same-sex couple embracing each other and clicking a picture in front of the Lotus temple in Delhi. This image is interesting in two ways: firstly, this is a statement of the presence of same-sex relationships in India, a rather radically new iconography from the traditional normative gendered images usually seen to characterise such pictures. Secondly, they depict the woman in the public sphere, not within her domestic confines. Thus, although there are examples of females showcasing their sexuality, usually as a courtesan or a controlling wife, they are usually confined to a domestic space, signalling a sort of female invisibility in the public sphere traversed by elite men. The second image is Patua’s depiction of the Nirbhaya incident, which caused a huge public outcry throughout India. It seems the creator wishes to participate in the protest movements that rocked the entire nation but in a language and medium feasible to him. The image inevitably draws viewers’ attention to the startling brutality of the crime.

Nirbhaya, painted by Kalam Patua | Watercolour on paper | Google Arts and Culture

Thus, instead of simple tales of mythology or a caricature of the new women, he uses a model all too familiar but subsequently forgotten, i.e. the depiction of contemporary events, as in the case of the Elokeshi murder. The depiction of Nirbhaya portrayed the artist’s sense of justice and morality, which interestingly differs from the historical treatment of such issues in older Patachitras by Kalighat Patuas. While the Elokeshi images generated ideas about subaltern consciousness and the fall from traditional notions of morality, Kalam Patua, working closely with modern and contemporary art spheres, shows how his own consciousness as an artist has changed over time to depict the feminine in a radically new way in Patachitras.

References

“APT8: Kalam Patua's contemporary storytelling - QAGOMA Blog.” QAGOMA Blog, 5 February 2016, https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/apt8-kalam-patuas-contemporary-storytelling/. Accessed 24 February 2023.

Archer, W.G. Bazaar Paintings of Calcutta, the Style of Kalighat. London, H.M.Sationary Office, 1953.

Sarkar, Tanika. Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism. Hurst, 2001.

Thakurta, Tapati Guha. “Women as '' Calendar Art" Icons, Emergence of Pictorial Stereotype in Colonial Art.” Economic and political weekly, vol. 26, no. 43, 1991, pp. WS91-99.

Subhrodal Ghosh is a postgraduate student of History at Jadavpur University. He is a theatre activist, and music enthusiast who loves to explore cultural nuances through art and literature.