"I am a reaper whose muscles set at sundown."

[Harvest Song – Jean Toomer]

A few seconds into the art space of Arindam Chatterjee's solo exhibition at Emami Art, one encounters a trajectory of bodies that defies the norms of any form. The deformed, fluid, and tightly bound human bodies and their positioning with other bodies that may be "human" or "abhuman" reach us with such malleability that they elude any categorization. Masses of matter standing on the threshold of human and non-human bring forth not only the posthuman fear of inevitable extermination or the fear of tumbling down the ladder of evolution but also the spectre of bodies that perhaps were anterior to human subjectivity.

The dull buzz of the elevator, the shuffling of hesitant or confident feet on the polished white floor, the whispers of fellow viewers, and the faint clicking of selfies fade away as one confronts bodies that seem blatantly surgical in their intense materiality. Stitches, folds, blemishes, cuts, discolouration, loose muscles, and knotted spine greet viewers unabashedly. Bodies twisted, doubled up and pierced, with backgrounds of vacant lots, a patched-up ship, fire, smokestacks, and stunted dried trees make for an uncanny arrangement ironically set in a sanitized neat art space.

I have never been able to place Chatterjee's works within a conventional meaning-making pattern. The figures of his works seem to perch on hypnotic moments that are paradoxically too close for comfort and yet too alien to grasp. Their impact lingers. Likewise, in this exhibition, some images stayed with me long after I exited the building.

A figure on all fours crawls forward with a lifeless face and eyes that gaze upward as if surprised in Fragile Existence VI [fig. 1]. I wonder whether the eyes are open or if the figure is blindfolded. The skin is too loose and creased, as if Buffalo Bill has let his victim out for one last crawl before the flaying begins.

Fig. 1. Arindam Chatterjee, Fragile Existence VI, 2022. Image courtesy Emami Art.

A woman (or a man? or a flamingo?) is set against a dreary brown room in Metamorphoses II [fig. 2]. The precarious posture of the figure, its crossed hands, curled toes, and the plant on a tub weave a bizarre thread of visual matches. The plant is perhaps the only undistorted shape in the entire collection of Chatterjee's works at the exhibition. Its muted green set against a grainy brown and grey background brings into sharp relief the unruly materiality of the fleshy pink and white of the human-like figure's femur, tibia, and fibula.

Fig. 2. Arindam Chatterjee, Metamorphoses II, 2020. Image courtesy Emami Art.

Two identical figures in red, consuming each other's feet in Mute Longing III, quite disconcertingly made me think of what people term as "love" [fig. 3]. Strangely, I remembered Mrs. Bates and her doting son, Norman Bates, of Hitchcock's Psycho – each consuming the other, each grotesquely emerging from the other.

Fig. 3. Arindam Chatterjee, Mute Longing III, 2019. Image courtesy Emami Art.

Another frame with two identical red and black figures from the same segment smiles at the viewer [fig. 4]. It could be the Joker’s eerie smile or an uneasy reminder of the penultimate shot of Psycho again, where the son's face dissolves slowly into the Mother's grinning skeleton. Two faces are looking straight at the viewer with grotesque smiles.

Fig. 4. Arindam Chatterjee, Mute Longing II, 2019. Image courtesy: Emami Art.

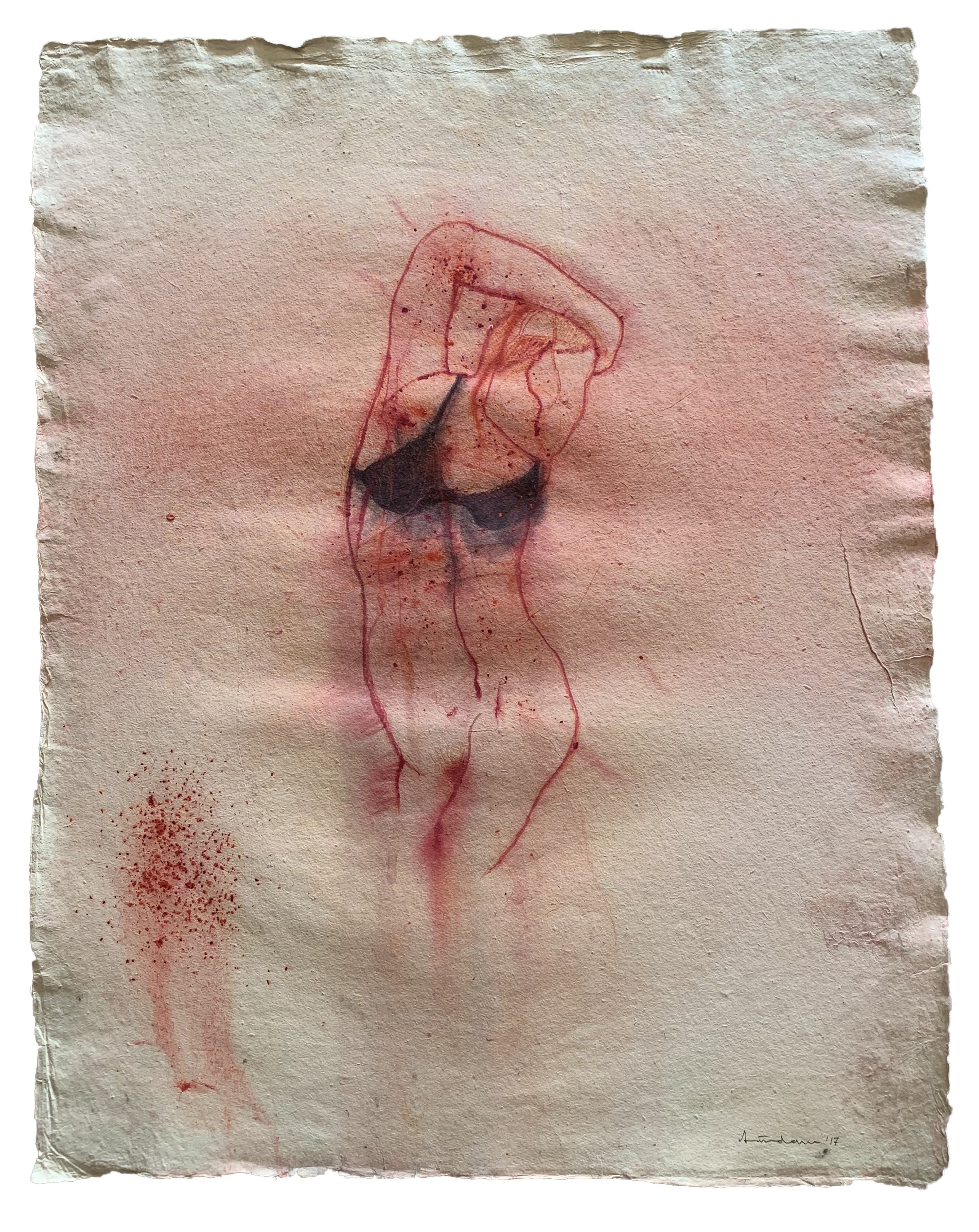

The red, scarred and faceless female figure with a black brassiere in a warped gesture of seduction again from the section titled Mute Longing I reminded me of the corpse of Myrtle Wilson in The Great Gatsby bashed by the car of her lover in her one last attempt to make him notice her [fig. 5].

Fig. 5. Arindam Chatterjee, Mute Longing I, 2017. Image courtesy: Emami Art.

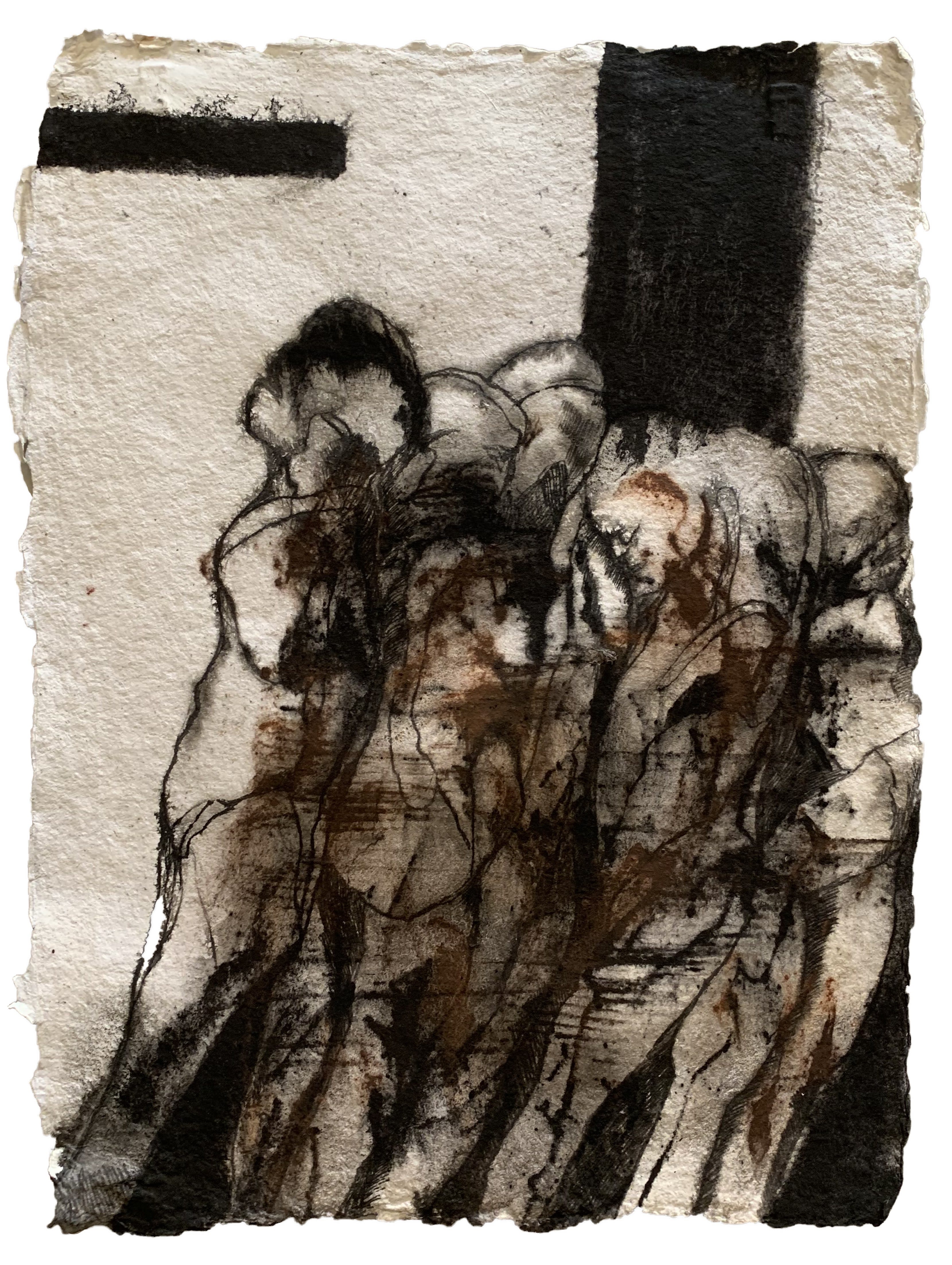

Again, the undifferentiated mass of men (where the borders of one figure seep into another) in Fragile Existence I who muddle together, waiting perhaps to be converted into dead bodies, brought to mind the piles of bodies in the black and white stills of Night and Fog [fig. 6].

Fig. 6. Arindam Chatterjee, Fragile Existence I, 2022. Image courtesy: Emami Art.

While dead bodies seem strewn all around, many frames also pulsate with disturbing experiences of being alive through visuals of pain and fear. The first few frames with rhizomatic bent men, men without faces yet with prominent ribcages, sinewy coverts of bird-shaped flying creatures, bodies clubbed together with their skin rubbing and prodding each other, compel us to shift from a visual world to a tactile one. As we proceed, we encounter a sharp-fanged reptilian creature about to bite a man's extended finger, a one-legged trunk of a man pierced with a spit ready to be roasted, and non-humans pierced or tied by human-shaped organisms. The images narrate unrelieved actions of pain and foreground corporeal parts that trigger immediate haptic memory. The brute corporeality in its extreme depiction of mutability and vulnerability in each frame renders the very state of embodiment unfamiliar, catapulting us into the world of Body Horror. The fact that it is impossible to label any body precisely in any of the frames present in the exhibition can be a potent source of fear and bewilderment. Extreme torture, dismemberment, and gore-fest are not always needed to turn our stomachs inside out in a Body Horror, as Chatterjee's art amply demonstrates.

Feet that can barely support the burden of a sluggish, unyielding body, neck arched forward with its sinews, adjuncts, and nerves messed up in a silent cacophony of red and grey, and tangled fragile spine unable to bear the Weight of Heaviness are frequent in many of Chatterjee's works displayed. Thus, the body parts crucial in making a human stand tall and upright are ineffective and deformed. These images of corporeal fragility make a viewer acutely conscious of his/her/their condition of embodiment and its contingent nature. While the crawling figure from Fragile Existence VI may remind us of Buffalo Bill's victims in Silence of the Lambs (the "other" with whom we have a safe distance) the precariousness of the fragmented bodies with stakes, spits, and ropes perhaps invades our skin, our flesh, our muscles and our bones.

The bodies, therefore, come to us as "others". The bodies also come to us as "us". The bodies come to us as humans. The bodies also come to us as "abhumans". The bodies come to us as "living" to make us intensely aware of our materiality. The bodies also come to us as "corpses" – not as material remains but as material that remains.

AUTHOR PROFILE

Subarna Mondal is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at The Sanskrit College and University Kolkata, India. The author has completed her PhD from Jadavpur University, Department of Film Studies, India. Her areas of interest include late-Victorian Gothic literature, the Gothic on screen, and the films of Alfred Hitchcock.