It’s KG Subramanyan’s birth centenary, and all over the country, we have various exhibitions popping up as a tribute to the master artist’s life and oeuvre. One such show is One Hundred Years and Counting: Re-Scripting KG Subramanyan, a research-based survey exhibition curated by Nancy Adajania on the ground floor at Emami Art – a gallery which also doubles as my workspace as an assistant editor at the establishment.

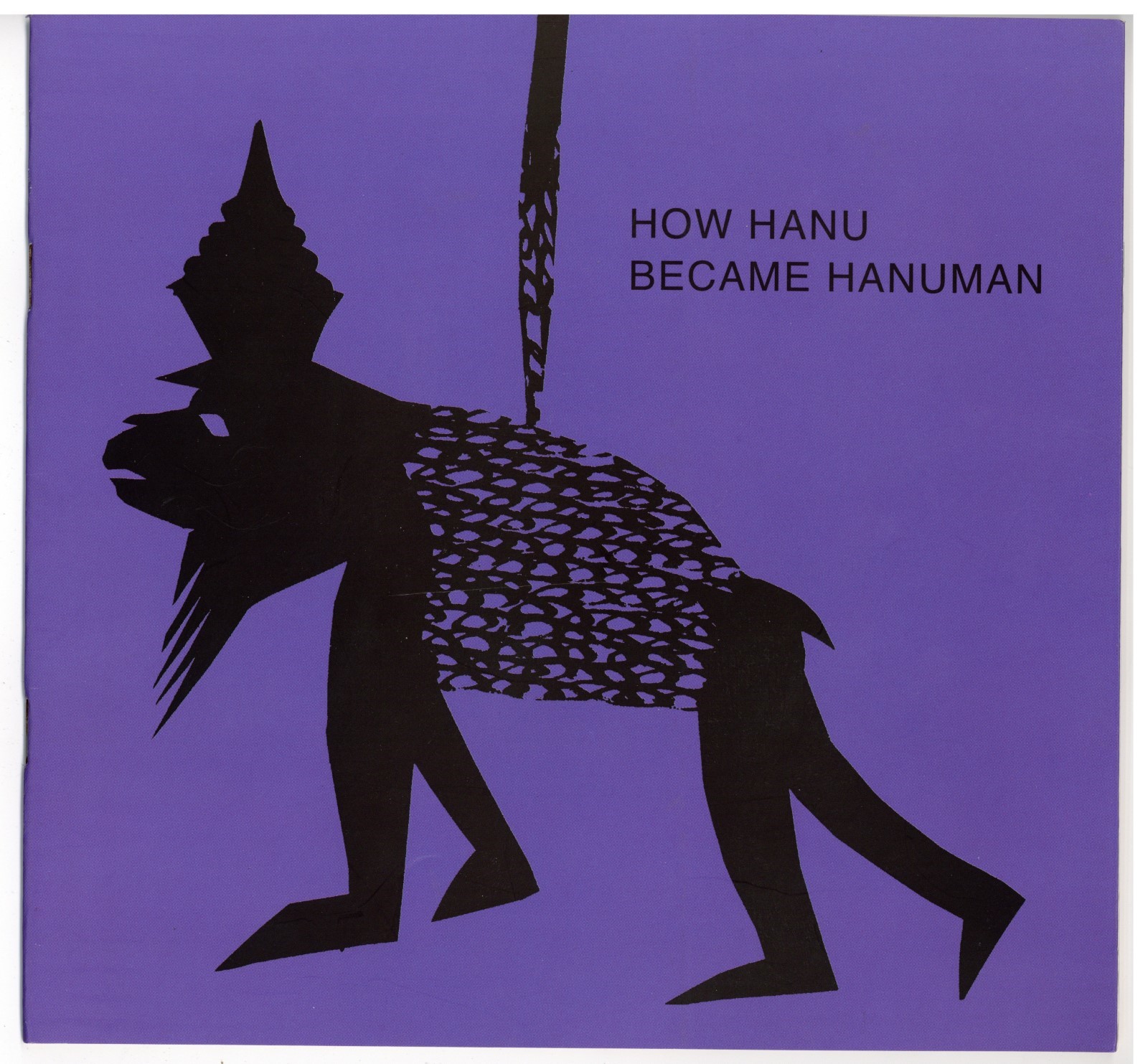

The hours are long, and the exhibition is voluminous – covering seven decades of KGS’s practice as a painter, muralist, author, illustrator, printmaker, sculptor, and activist, and as I sit surrounded by a collection of ten of his illustrated books for children, this one book with a bearded, crowned, rather exalted ape lumbering across the cover has my attention (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The cover of How Hanu Became Hanuman.

How Hanu Became Hanuman. It is the title that catches my eye – this hint of a character arc, the use of “man” not as a part of the protagonist’s original name, but as somewhat of an honorary suffix – something that changes Hanu to Hanuman, thus making the resulting name similar to the superheroes in popular culture: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, and the like.

My interest is intensified by the fact that on the wall perpendicular to me is an archival handcrafted mockup of How Hanu Became Hanuman displayed as part of the exhibition – a series of 13 never-seen-before collages of black and brown chart paper cutouts. The book, first published in 1995 at the Fine Arts Fair by the Graphic Art Department Faculty of Fine Arts, MS University, Baroda, and then by Seagull Books in 1996, is brighter than the mockups – the illustrations now more orange and white than brown and beige. However, the mockup, as the exhibition’s curator Nancy Adajania puts it, is an excellent way for viewers to know how KGS composed his collages with humble materials and designed the layout with free-form graphic elements for his young readers. Adajania also regards KGS’s children’s books as a vessel for the majority of his political philosophising, which is why a closer look at Hanu (and in turn, KGS’s politics) becomes necessary.

The story, if the title was any indication, is a retelling of the Ramayana, narrated as a humorous Bollywood-style superhero flick. Raghu’s girlfriend has been abducted by ten ruffians in a helicopter, and he comes across Hanu while looking for her. Hanu explains how he has superpowers – powers that were lost when some apes developed “an extra dose of brain” and became human, which makes him the perfect candidate to go retrieve the girlfriend, instead of Raghu. Hanu finds Raghu’s girlfriend at a disco on a remote island, fights her, knocks her out of consciousness, and carries her back to a thoroughly impressed Raghu, who wastes no time in putting the ape on the same pedestal as the superheroes of his childhood.

The Bollywood trope begins on the very first page itself and continues throughout the rest of the story. “Raghu met Hanu in a dense jungle,” writes KGS, “Hanu was lounging on the branch of a tree and looking at a string of pearls” – and the only image that immediately pops up in my mind on reading this line is that of Kalibabu in Devdas (2002), stretched out at the brothel with the smug self-importance of an obnoxious, upper-caste landowner. Hanu, of course, isn’t a zamindar, but he doesn’t quite beat the obnoxiousness allegations either, as seen in the following pages.

The superhero trope, on the other hand, solidifies when Hanu brags about his abilities to Raghu (Fig. 2), establishing himself as a shape-shifting force to be reckoned with: “I can jump from tree to tree, I can float in the air. I can smell and see across a continent. I can shrink to the size of a flea and swell to the size of a cloud. I can crush rocks between my fingers and cross the seas in a leap. Don't, my dear, underestimate your ancestor.”

Fig. 2. KG Subramanyan, Mockup for How Hanu Became Hanuman 6, 1995.

Fig. 2. KG Subramanyan, Mockup for How Hanu Became Hanuman 6, 1995.

Image courtesy: Seagull.

What strikes me as interesting is the fact that while Hanu is exalted as a lifesaving valorous wonder ape and Raghu is seen as the worried boyfriend, Raghu’s partner (who logically should be Sita) remains unnamed throughout the book. The Bollywood-like plot makes perfect sense then, for the story carries the same stereotypes as the standard mainstream Hindi film. This identityless damsel in distress, despite being a black-belt in martial arts, has neither agency nor lines – she is as silent as she is useless, her only role is to be saved so that Hanu can be hailed as a saviour.

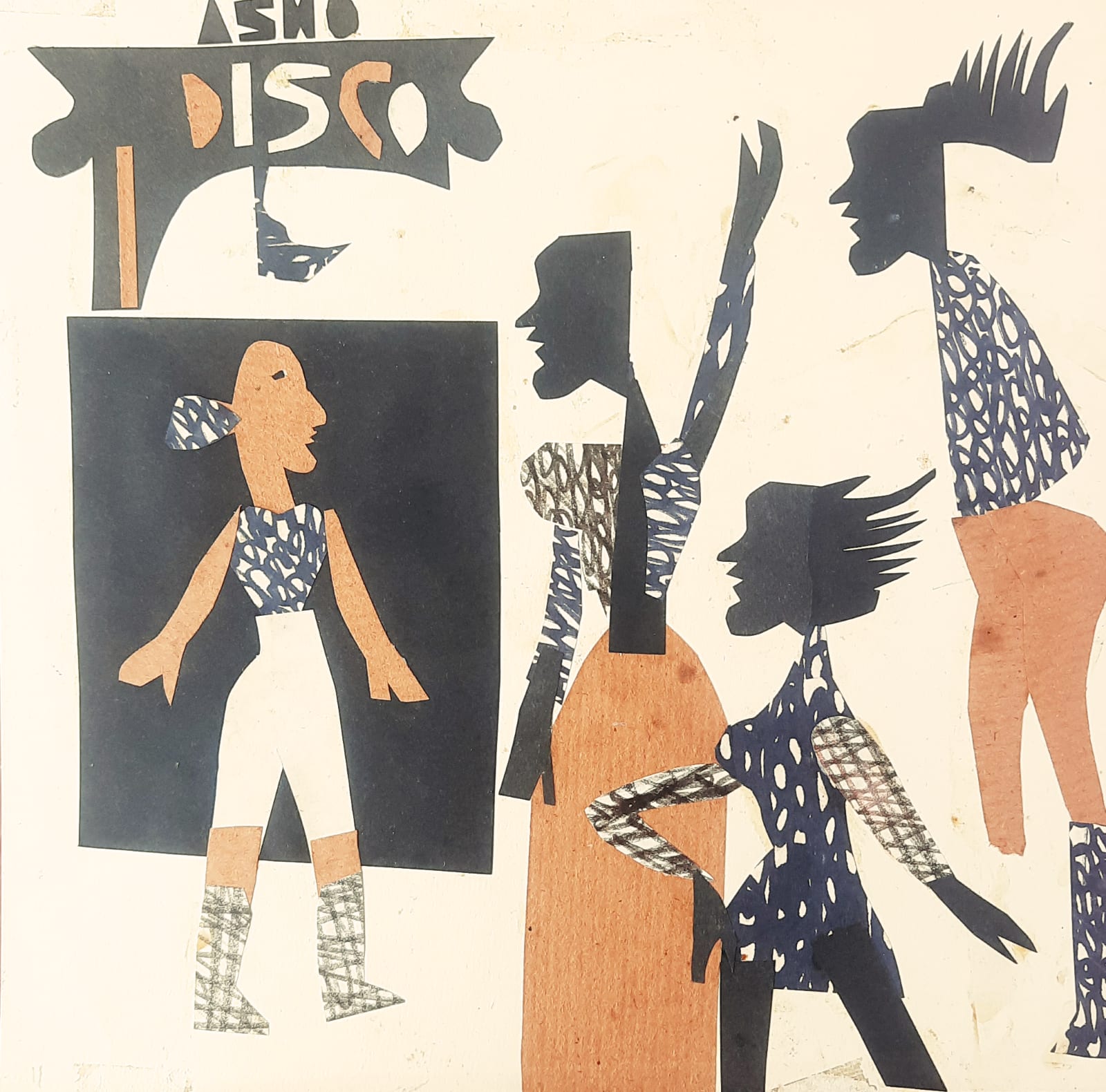

The portrayal of women only gets more concerning as the story proceeds. The “bulging beauties” surrounding Raghu’s girlfriend at the disco persuades her to become like them, with “plucked eyebrows, blood-red lips, hair made a mess, bodies padded up” (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. KG Subramanyan, How Hanu Became Hanuman 10, 1995.

Fig. 3. KG Subramanyan, How Hanu Became Hanuman 10, 1995.

Image courtesy: Seagull.

Such descriptors reserved for female antagonists are common in KGS’s books for children – for example, in The King and the Little Man, we have the following lines:

“So came the queen

But who is a queen?

A queen is a woman.

Only an over-dressed woman.

She was padded and pearled.

She was painted and manicured.”

These are markers of contemporaneity, and of villainy – as KGS frames it, and this oft-repeated prejudice on the artist’s part is something that Nancy Adajania observes in her prefatory notes as well. Hanu, borrowing this prejudice, immediately knows how to “handle” the padded beauties on the island, and this “handling” is violent. He smashes the microphone, pulls out the wires, scares away the women, knocks out Raghu’s girlfriend for he decides that is the best way to deal with “black-belt girls”, and carries her unconscious form to Raghu – a supposedly rescue scene that reads more like an abduction. I daresay this treatment of the girlfriend is meted out as a sort of punishment for the way she is – a way that Hanu highly disapproves of. She is too empowered, and therefore must be restrained.

Because the mockup of How Hanu Became Hanuman is a part of the exhibition, and I too am situated at the Emami Art gallery while I write this, I cannot help but relate it with what is displayed on the wall adjacent to the collaged mockup – a video excerpt from Ritwik Ghatak’s Subarnarekha (1965). Adajania connects KGS’s pluralistic, polymorphic vision with the bahurupi (folk performer specialising in impersonation) in the film, appearing suddenly as the figure of the Goddess Kali, startling the young protagonist Sita (Fig. 4), who is then comforted and escorted home by a passing elderly man.

Fig. 4. Sita walking on an abandoned airstrip in Subarnarekha (1965) dir. Ritwik Ghatak.

While the curator meant for the clip to lend meaning to the polymorphs in KGS’s reverse paintings, I believe another parallel can be drawn with How Hanu Became Hanuman. The book and the film, both retellings of the Ramayana, portray the rescue of Sita in widely different ways. On the one hand, Hanu physically assaults the woman and is still painted as a hero while she remains unnamed; and on the other, the man that little Sita bumps into while running away from the bahurupi, gently escorts her home and as they walk together, he tells her the story of the Ramayana – “shey ek Sitar golpo” (it’s the story of another Sita). He thus frames it as Sita’s story – she is the focal point of it all, not a male super-ape.

Raghu idolises this super-ape, and that, I'm afraid, tells us more about Raghu than anything else in the story. After Hanu brings back the missing girlfriend, she wakes up from her swoon only when she is thrown into Raghu’s arms and they promptly engage in a public display of affection (Fig. 5), much to Hanu’s distaste.

Fig. 5. KG Subramanyan, Mockup for How Hanu Became Hanuman 12, 1995.

Image courtesy: Seagull.

Hanu’s efforts in the rescue earn him a permanent place in Raghu’s heart (and workplace): “Raghu did not forget Hanu. He had three big posters above his posters about his chair in his office. Two were of Superman and Batman, heroes of his childhood. But above them, larger than life, was one of Hanuman, his real-life hero” (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. KG Subramanyan, Mockup for How Hanu Became Hanuman 13, 1995.

Fig. 6. KG Subramanyan, Mockup for How Hanu Became Hanuman 13, 1995.

Image courtesy: Seagull.

However, if Hanu is the kind of individual Raghu looks up to, it makes one wonder how Raghu would turn out to be as a person/partner.

KGS’s books for children, like most other books made for children, cannot be limited to a singular age group, for the stories hold meaning, morals, and hopefully, questions for their adult readers as well. Be it a novel or a funny 18-page story of a wondrous ape and his shenanigans punctuated by the most delightful illustrations, it is up to us to sift through the motives of the characters and the purpose of the plot. Hanu, as it turns out, has a long way to go before he can truly be a child’s hero.

AUTHOR PROFILE

Sriza Ray is a postgraduate in English Literature from Presidency University, and currently works as an Assistant Editor at Kolkata Centre for Creativity. She harbours an interest in all things related to art, literature, research, and publishing. Above all, Sriza is passionate about mountains, museums, and maintaining a list of names for her future pets.