“Ab Nishane Ishq

kalkatta mein garwa chahiye

Husne Shahar-e-lucknow

Hardum ujaane chahiye”

~ Wajid Ali Shah

Translation - All the love that I have for beloved Lucknow should now be poured into Calcutta

Figure 1 MAIN ENTRANCE OF QASRUL BUKA IMAMBARA

Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Lucknow/Awadh, spent his exile in Metiabruz in Calcutta (1856-1887) following the annexation of his beloved kingdom by the British. Matiyaburj (matiya means mud and burj means fort) an area on the banks of Hooghly River in the southernmost fringes of Calcutta was a part of the Sundarbans, inhabited by the Bangla-speaking low caste Hindu community— mostly farmers, fishermen, tailors—who had settled there and converted to Islam around late 18th century. With the advent of the nawab and migration of a huge population from Lucknow consisting of members of the royal family as well as musicians, dancers, tailors, cooks, and artisans among others, Matiyaburj was given a new identity – Chhota Lucknow, where nawabi culture (tehzeeb/etiquette of Lucknow) made its presence felt in architecture, cuisine, language, music, literature and dress of the area. Most of the Nawabi properties were destroyed by the British after the Nawab died in 1887.

The contemporary Metiabruz, which is often derogatorily described as a Muslim ghetto, is home to Bangla and Urdu-speaking Muslim population, Bangla and Hindi-speaking Hindu families and a large working-class population most of whom have migrated from Orissa and Bihar to work in the shipbuilding company and Khidderpore docks. In contemporary Metiabruz, what remains of the Nawabi culture is a complex question. This write-up focuses on the few ‘nawabi’ architectures left in contemporary Metiabruz.

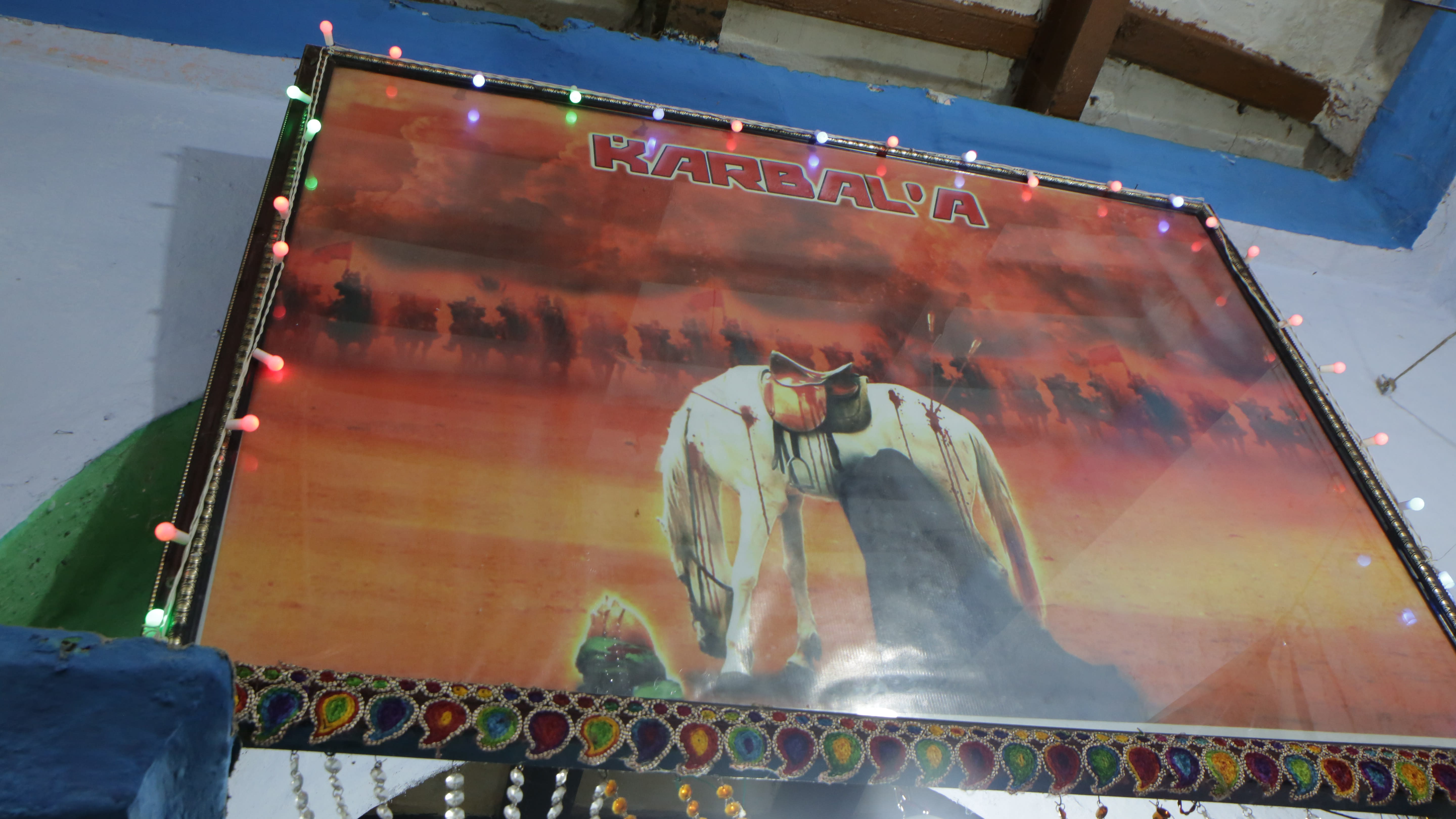

Figure 2 INSIDE QASRUL BUKA IMAMBARA PHOTO ABOUT KARBALA WAR

Figure 3 INSIDE QASRUL BUKA IMAMBARA (A WATER CARRIER)

As one approaches the main Garden Reach Road from Khidderpore, one finds the Qasrul Buka Imambara. It is extremely difficult to locate it as the old architecture can hardly be seen from the outside. The Imambara is almost hidden among different shops factories and old buildings. However, the interiors of the Imambara take us to a different world. It is adorned with chandeliers, lamps, scenes depicting the Karbala war and colourful tazias. The newly installed clock tower, standing almost opposite the Imambara on the main road along with the bazaar, residences, schools and densely populated lanes of Metiabruz creates a contrast with the nawabi architecture of the Imambara.

Figure 4 OLD PILLAR OF SHAHI MASJID

Figure 5 RENOVATED PILLAR OF SHAHI MASJID

As one keeps walking further on the main road one comes across Iron Gate Road, on the right-hand side. Shahi Masjid, the place for nawab’s worship is located here. It bears remnants of old architecture—the old pillars lying in the backyard—and the renovated pillars adorned with designs in red, green and golden colour on a milk-white base. Much like Qasrul Buka Imambara, Shahi Masjid with its quaint prayer hall, the wuzu pond, the simplicity of design and the quiet ambience presents a stark contrast to the rapidly changing landscape of Metiabruz.

Figure 6 SMALL POND FOR WUZU AT SHAHI MASJID

Sibtainabad Imambara is located further down the Garden Reach Road. The grand and impressive gateway consisting of the double fish, the royal emblem, sets it apart from the rest of the buildings which have sprung up in the later decades. The entrance leads to the courtyard decorated with potted plants and flowers on one side and a big gong on the other. Then one crosses the long veranda before entering the main hall. The family tree of the Nawabs, an old clock, and important newspaper reports are placed on the veranda. The main hall consists of the nawab’s tomb, the royal seal, the Quran and different tazias. The decorative chandeliers, old photographs, the intricate drawings on the glass door, and the use of blue and green against the white walls add to the grandeur of the edifice.

Being a devout Shia Muslim, Wajid Ali Shah introduced Muharram in Calcutta which is still celebrated with vivacity and the Imambara witnesses a huge congregation during the festival. As one sits on the veranda of the Imambaraone notices India’s national flag flung from a great height from the premises of the Garden Reach shipbuilding yard, located opposite to the Imambara.

Figure 7 OFFICIAL SEAL, QURAN, TAZIA AT SIBTAINABAD IMAMBARA

In each instance, the past and the present sit face to face, time meets time to (re)define the now-ness. The visual signs of the nawabi era scattered across the area are a constant reminder of the convergence of displaced communities who have settled in Metiabruz at different temporal junctures. An understanding of the contemporary Metiabruz entails deep engagement with these communities and layered time(s) which engenders the cosmopolitanism of the area.

Figure 8 NAWAB WAJID ALI SHAH’S TOMB AT SIBTAINABAD IMAMBARA

All Images courtesy of Susmita Sinha

Bibliography:

Mitra, S. 2017. Pearl b the river: Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s Kingdom in Exile. New Delhi: Rupa Publications.

Mukhopadhyay, D. 1984. Ayodhyar Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. Calcutta: Shankya Prakashan

Nandi, J. 2005. Present and Past of the Community-based Garment Industry in 24 Parganas (South) of West Bengal, Final Report.

https://indianlabourarchives.org/xmlui/handle/20.500.14121/2592

Sharar, A.H. 1974. Guzeshta Lucknow. (trans.) G. Bhattacharya. and M. Khatun. New Delhi: National Book Trust of India.

Sreepantha. 1990. Metiaburujer Nawab. Calcutta: Ananda Publishers.

Tapadar, A. 2002. Kolkatar Chhota Lucknow. Kolkata: Subarnarekha.

William, R.D. 2023. The Scattered Court: Hindustani Music in Colonial Bengal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

AUTHOR PROFILE

Shruti Ghosh is a Kathak dancer, choreographer, teacher, and independent researcher based in Kolkata, India. She is recipient of Arts Research Grant from India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore and is researching on legacy of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah and cultural memory of exile and identity formation in Metiabruz. She was a former dance teacher and performer at Indian Cultural Centre, Embassy of India, Kazakhstan (2018-2020). Shruti has performed in London, Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, different parts of Kazakhstan and India. She has published in many journals and anthologies on film music, film dance and theatre. Currently, she is performing three solo pieces Khol Do (on partition of India and sexual violence), Juddho Keno hoi (on different aspects of war) and Barnoporichoy (stories of women emancipation) in different parts of India.