Artist Dilip Mitra is a Professor at the Department of Painting, Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan. He grew up in a refugee colony in Belghoria, Calcutta, in the 1960s, but it was only as a young adult that he realized that the life he had known was different from the other denizens of the city he grew up in; and that distinct colony experience became the inspiration for his art once he started practicing. While his paintings on the subject are extensive, there is also a diary full of sketches of his childhood memories of the place and its people – a veritable treasure trove from his past! They are the meditation of an adult man remembering the child universe of a refugee colony, where the predominant memory is not of deprivation but being surrounded by the loving care of elders and being a keen observer of the life around. The result is an unconscious ethnography of a place – from the layout of a home to the actual huts of the extended family, from activities related to certain livelihoods in the neighborhood to objects of daily use; and finally, and perhaps most importantly, affectionate portraits of family members who made up the fabric of his life.

Men outnumber women in Mitra’s diary; and the one who predominates among them is his ‘’boro jethamoshai’ or ‘boro jethu’ – his father’s eldest brother. His father was the youngest of three brothers, all of whom find a place in the diary. The difference in their lives, owing to their professions and distinct temperaments, come out strikingly in these hasty portraits.

Boro jethu held a special place in the artist’s heart when he was a child. He ran a laundry shop and had ample leisure time which he devoted to the children of the house and pet animals. All the three pages of the diary devoted to him are replete with that aspect. Thursday was his day off when he would tutor and mother the children, teaching Maths to reluctant boys (who dreaded the ‘namta’ or reciting the tables part) and taking them to the pond to bathe after a thorough massage of their hair with mustard oil. While in the pond, their lessons would continue – in swimming this time, the initial bit of which was to hold on to bamboo branches half submerged in the water to practice stationery paddling.

He loved animals, particularly domestic ones. In more than one sketch, he is seen bringing home a little bird in a cage, carrying it on his right hand while holding an umbrella on his left hand or armpit. The chicks of ducks were another favorite of his. He would not only take care of them at home, but like his nephews, take them out to bathe in the pond as well, playing with them in the water for an hour or two and protecting them from crows circling above. The latter scene is sketched elaborately in one instance, which also gives details of underwater life – filled with fish and its eggs, strewn leaves and the abandoned branch of a betel tree that cuts diagonally across the page (Sketch 1).

Sketch 1 - Boro jethu 1

Boro jethu was particularly affectionate towards little Dilip, encouraging his drawing skills by periodically giving him newspaper cutouts for him to draw and practice. The nephew was a keen observer: he found the uncle’s doodles on his bill-books very interesting and was particularly fascinated by how well he sharpened the pencil that he used with a knife, beating any sharpener that they could have had. His own talent for drawing came from his uncle, he believes.

There were also certain idiosyncrasies that did not miss the nephew’s observation: after his bath, Boro jethu would pace up and down his room wrapped casually in his dhoti (folded up half like a lungi), reciting shlokas from the Bhagavad Gita at a stretch (Sketch 2).

Sketch 2 - Boro jethu 2

The boy’s ‘Mejo jethu’ (or second eldest paternal uncle) did not live in the colony. A foreman in the Bhillai Steel Plant, he lived and established himself in that industrial city and would visit his brothers and their families once in a year or two. His nephews would look forward to two things during those visits – a crisp, brand new one-rupee note that he gifted them and the ‘Hing-er kachuri’ (fried dumplings using asafoetida) that they had on their mandatory visits to the Dakshineshwar temple with him. We get to know this in a caption; also, that, decades later, when a young Dilip went to meet his very old uncle, he was struck by the changes that old age had wrought on him – stooped shoulders, an inattentive look on his face, though the smile intact at the joy of seeing him. That would be his last visit to Bhillai, the last time they saw each other. We see this old mejo jethu standing at his gate, memorializing the moment of goodbye. Elsewhere, just his young and old versions stand side by side: the young man dressed well in formal shirt and trousers and Bata sandals; and the old one, wrinkled and stooped very low, attired in home wear. A dark figure rises like a shadow above them… which is open to interpretation.

The artist’s father was a doctor. He used to practice homeopathy on the side. And though he wanted to study MBBS, he could not afford it. He however managed to become a ‘RMP’ – a Registered Medical Practitioner, having a small chamber in Kamarhati, a predominantly Muslim locality. His fees was nominal, only a few annas. And every afternoon, when he came home to eat and nap, he would ask his son to count the coins kept in a little ‘putli’ (pouch). The little boy did that eagerly enough and would also polish the father’s shoes. The doctor’s bag was an integral part of him, as was his cycle, with which he went to work and did his rounds (Sketch 3).

Sketch 3 - Baba

Of the three brothers, little Dilip was most afraid of his father and felt closest to his eldest uncle.

Another male figure we encounter in the diary sketches is his cousin, ‘Shanti da’. Son of his widowed paternal aunt, Shanti da (short for ‘dada’, or elder brother) was known as a private tutor and would give endless tuitions in the evenings, in the light of a hurricane lamp. He is shown in various sitting postures – reclining against a pillow, bending slightly over a book, but always cross-legged: his right hand resting on his left ankle, his left placed on his knee (or held up to dig his nose!), curly hair framing his head and broad/dark-rimmed specks his face, which is shown in profile in all the three iterations on the same page. The kerosene lamp - the devise through which he earned his living - is given prominence, with two of them accompanying the three figures.

The female figures we encounter in these diary pages are equally interesting. His ‘thakuma’ (paternal grandmother) makes only a cameo appearance on a page filled with his boro jethu’s sketch. Placed at the top, we see her lying in bed, head on a pillow, legs folded up in the air! She is almost completely bare, save for a cloth casually covering her groin; her sagging breasts and wrinkled skin exposed to view. She is fanning herself with a palm-leaf fan, her hands raised over her head. This tiny sketch is as realistic a portrait of old age as can be – comic and affectionate at the same time.

The boy’s mother and ‘jethima’ (wife of boro jethu) we find in a pond, late at night, during the monsoons, come to forage for ‘shoal machher pona’ - or baby shoal fish - that could become a free resource for their next meal (Sketch 4). Refugee life meant a spartan existence – in terms of space, food, and clothing. Thrift was unavoidable, and ingeniousness a necessity. Every available resource had to be made use of, and nothing was discarded when it came to food – leaves, stem, or skin. Instead, they were made into delicious dishes that were proudly handed down to the next generation.

Sketch 4 - Ma & Jethima

Another woman we come across in the diary is the artist’s Monu ‘pishima’ (youngest paternal aunt). Ever since he had sense and could remember, he has seen his aunt a bit hunched. A widow who lived in a nearby plot, she would frequently visit her brothers’ families, coming in a rickshaw. We see her hunched figure in outlines, sitting-standing-walking, the drape of her saree emphasized in some, and the prominent mole on her left cheek visible in all.

Little Dilip grew up amongst many cousins. His boro jethu had four daughters, who were all much older than him. Three of them feature in one page, all together, sketched on an ascending plane, though not in order of age. They are all draped in sarees, with a bindi on their foreheads and sandals on their feet – facing us frontally, unlike most other sketches in profile. The middle sister on the left is holding a toy, the youngest standing in the middle has a handbag, and the eldest on the right comes with a caption: “She was the best in studies amongst us, with a double MA. She was like a shadow of my mother, looking upon this younger aunt (kakima) of hers as her own mother”

In the colony, every hut had a mud oven in their ‘uthon’ (or courtyard), where clothes would be boiled in soda in a huge iron kadai, as part of their washing – the water sometimes mixed with cut pieces of soap that was called ‘ball-saban’. This detail accompanies the portrait of the three sisters.

We meet 11 members of the Mitra family and extended family in these diary pages. Though they had separate huts within the colony, they all lived close by - by conscious design - which enabled the brothers to function practically as a joint family.

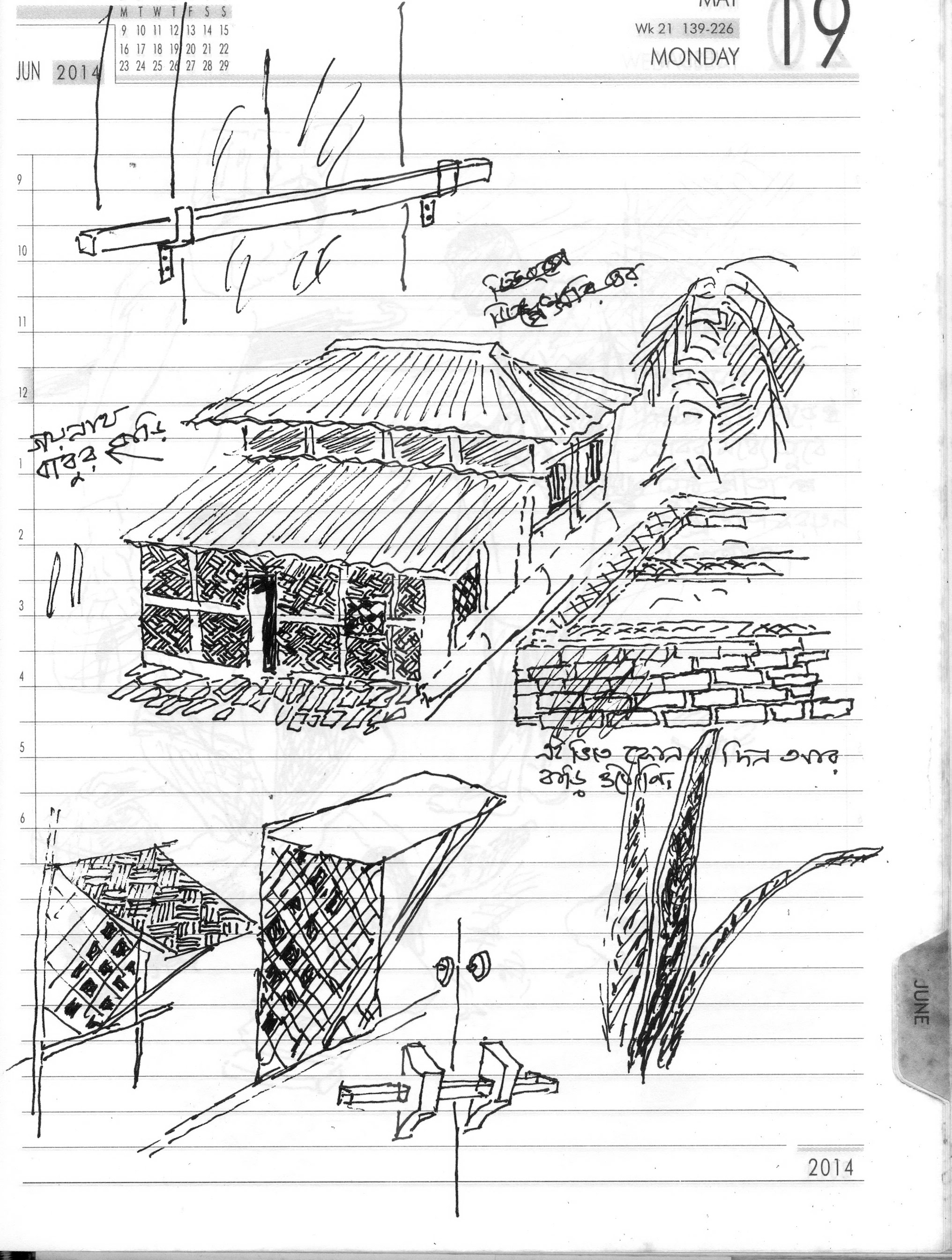

Some of the prettiest sketches in the diary are those of huts and houses. And the neatest page among them represents Goynath babu’s home. Its highlight is the ‘berar janla’, or window made of bamboo (immortalized by Ritwik Ghatak in his film Meghe Dhaka Tara, where the refugee protagonist Nita looks through it, at several crucial moments of the film). We also find a detail of it at the bottom, which shows a mechanism by which it could be pushed up or down. Other details surround this home – of a plant, a door lock, a door bar that kept the door shut when placed on its double rim. But the intriguing part of the page is another thing: adjacent to the home of Goynath babu, we see an empty plot with only the foundational bricks of a house-to-be – a ‘bhite’. But no house ever came up there (Sketch 5).

Sketch 5 - Huts 2

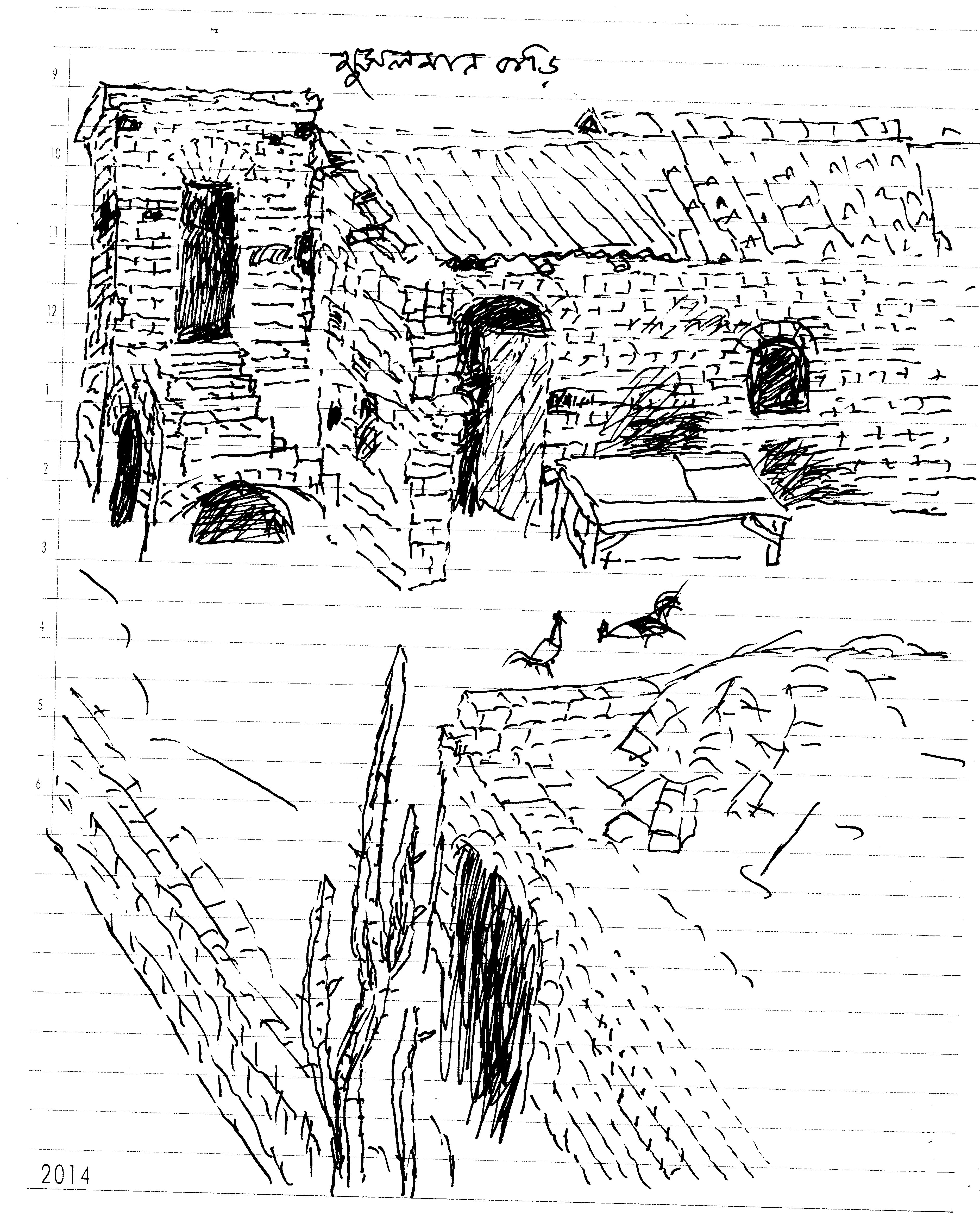

As opposed to this ‘bhite’ that never came up, was the abandoned house of a Muslim owner (featured in another page) where no Muslim lived. The family had possibly left for East Pakistan, even as refugees came from there. It was inhabited by eight to ten Hindu households, Mitra remembers, who used gunny sacks to partition their space (Sketch 6).

Sketch 6 - Musalman bari

We also see a bunch of huts belonging to different members of the extended Mitra family, surrounded by trees, and hemmed in by a hedge.

A layout of a huge plot of land makes for an interesting study in another page. Here, the artist has turned architect, laying out a portion of a neighborhood in geometric lines. What is most arresting about it is the number of trees that dot the plot of land – nishinda, jamrul (java apple), jaam (black plum), dumur (cluster fig), khejur (date), tal (toddy palm), peyara (guava)… you have it all. Not to forget the ‘tulsi mancha’ without which a Hindu house was incomplete.

One of the most unique diary pages is where a decorated stage stands empty, with a bulb and loud speaker. Printed sarees double up as curtains on both sides. A young person stands alone near the stage on the right, presumably getting things ready. This is a moment of anticipation, before the performance begins – with neither performers nor audience in the venue; and this scene, a remembrance of the plays that were staged annually by the children of the colony, in the artist’s aunt’s courtyard.

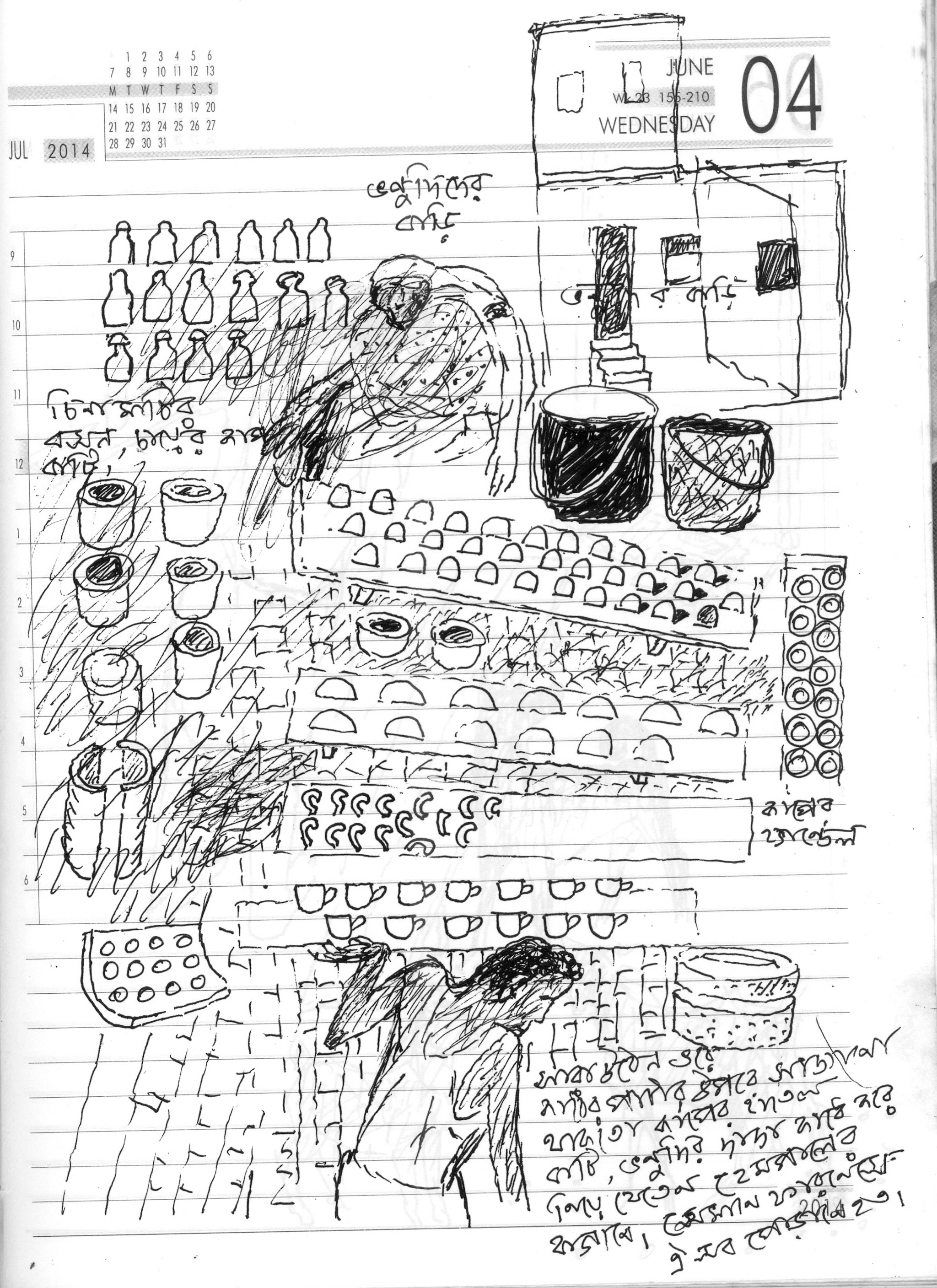

The colony nurtured a number of peripheral livelihoods; several pages of the diary attest to that. One focuses on welding; we see a man sitting hunched over, a welding rod on his right hand, a welding shield on his left. But he is in the background. In the foreground, we find the zoomed-in representation of the gas cylinders that enable his work. In another, we see a ceramic shop, situated within a house (‘Bhonu didi-r bari’), where ceramic utensils – mostly tea cups and bowls, and cup handles – are arranged in three neat rows. Both Bhonu didi and her brother feature here, the latter taking the unfinished pieces to an industrial furnace close by, a place that was known to the children as ‘Hem Pal-er bagan’ (Sketch 7). Yet another page shows an elaborate process of glass tube manufacturing – from women working in the factory and items of manufacture to the lorry used for the transportation of the goods.

Sketch 7 - Ceramic shop

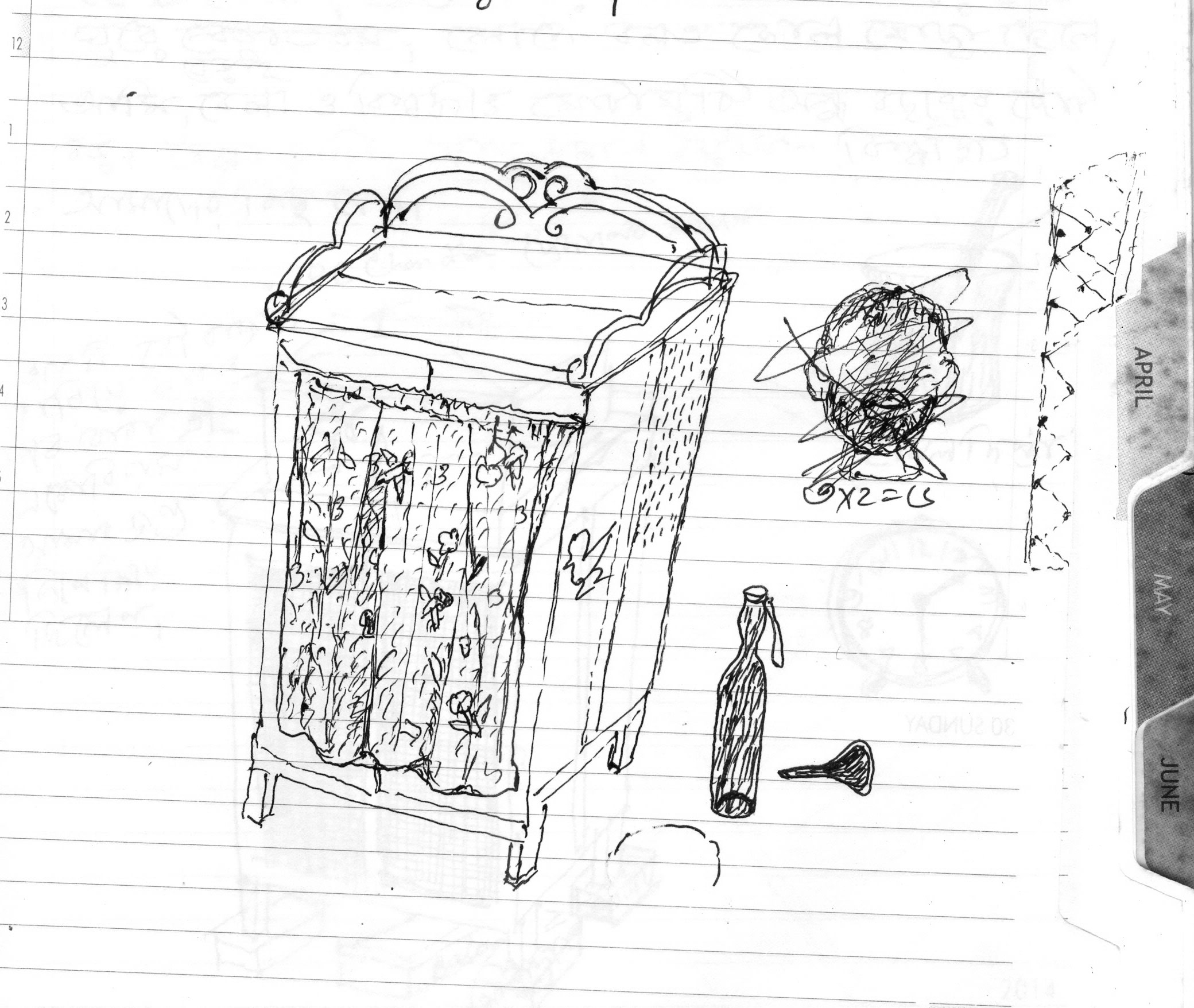

Several diary pages are also taken up with quotidian objects. The most prominent among them is a furniture that was used both in the kitchen and the bedroom: it functioned as a ‘meatcase’, with jali (or mesh) on the doors to keep cats out when food was stored inside; and his mother’s saree was cut down to size to make a decorative curtain over the door when used as a small wardrobe.

We see assorted other items: an alarm clock; a ‘haman dista’ which was used for grinding mustard during ‘Chaitra Sankranti’ (the last day in the Bengali calendar); a doctor’s bag and hat; a rolled up madur (mat); a trunk (with a cover on it); a hurricane, with its shadow; and a kerosene bottle, with the funnel to pour the oil lying on its side. Most of these items of daily use do not have any one particular memory associated with it. But there is an exception to that in one of the pages, where we see a crossed out face (Sketch 8). It is easy to dismiss it as a cancelled doodle, but for the story behind it. It is actually a replica of a drawing on the wall – apparently the face of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahansa – that the artist had done as a boy, but which was scratched out in an act of motiveless malignity by his mej-da (second elder brother). The two did not gel at all, and the elder brother was given to fits of such irrational behavior that hurt the younger one.

Sketch 8 - Objects 2

One may easily uncover a life of struggle and uncertainty from the subtexts of the sketches – the mothers foraging food on monsoon nights, the father resigning to the life of an RMP instead of being a certified doctor, the cousin relentlessly tutoring in the light of kerosene lamp, women working in factories, a Muslim home taken over by Hindu refugees where gunny-sack partitions are all there is to protect privacy. But what one is most struck by in this diary is the vividness of the childhood memories – of innumerable stories rendered in a mildly humorous vein through the medium of pen and ink. This essay is an attempt to bring those stories out of the artist’s studio.

AUTHOR PROFILE

Rituparna Roy is a writer based in Kolkata. She can be reached at royrituparna.com.