-

-

She who saw: A rich centenary tribute to Meera Mukherjee

Book Review by Rituparna RoyFrom the Depth of the Mould: Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998), a centenary tribute, is a rich compilation edited by Tapati Guha-Thakurta, with Adip Dutta and Sujaan Mukherjee as Assistant Editors. It brings a diverse array of material on the artist to give the most comprehensive survey of her practice and insight into the individual that she was. Five components cohere to give this holistic overview: a comprehensive introduction; essays on her craft, process and new directions in her practice; personal essays; translations of her diaries and unpublished reminiscences; and a stupendous collection of photographs covering a wide range of her sculptures – from small and mid-sized to monumental. All of it is welded together by the remarkable design of Sukanya Ghosh.

Five components of the book

Tapati Guha-Thakurta’s exhaustive introduction, in the form of a biographical essay, ‘Meera Mukherjee: A Life Apart’ – which could be a catalogue volume by itself – traces her long, difficult and unique trajectory as an artist, in seven detailed sections.

Adip Dutta’s essay, ‘Thoughts Cast in Metal: A Creative Pathway’, is a fine balance between a personal memoir of a mentor and a meticulous critique of a sculptor – especially in terms of the process of her work. It starts with an anecdote of how he had taken his first clay creation to her, it got partially damaged on the way, and she corrected it and made it better, but then crumpled it back into a lump without realizing his heartbreak. As compensation, she promised to make him another like it and that is how Sahodar [Brothers, 1992] was created.

Anecdotes – liberally sprinkled – in fact, build up the character of Meera Mukherjee throughout the volume. They surface in the conversation between Adip Dutta and Tapati Guha-Thakurta at the end of the book and the interview with Bandana Loharby Sampurna Chakraborty. But they are strongest in the three personal essays: by Samik Bandyopadhyay, her friend and associate; Sandipan Bhattacharya, her publisher; and Arun Ganguly, her Boswell. They give us an intimate glimpse of the person Meera was, with her idiosyncrasies, and the laborious process of her sculptural work.

Arun Gangily’s photographs constitute the bulk of the images in the book. Many of them have been drawn from the 2022 Exhibition of his photographs – “Meera Mukherjee by Arun Ganguly” – curated by Adip Dutta and Tapati Guha-Thakurta at Gallery 88, Kolkata and Project 88, Mumbai.

Translations

The most memorable part of the book is, however, the translations of Meera Mukherjee’s Diaries (1970, 1974, 1976, ‘The Bastar Journal’ 1960-61), and Unpublished Reminiscences – ‘A Visit to Japan’, 1983 and ‘Casting Season’, 1985-86.

While all these have immense archival value and are interesting in their ways, ‘The Bastar Journal’ stands out in the way it expresses her fascination for the place, the people, their lives and their art. It bears the impression of a new world opening up in front of her eyes. She is there to learn their traditional techniques of sculpting and she gives that her most devoted attention, as this passage from the Journal testifies:

The first step was to make the kuton or the inner core made of clay. Then, Manik [Gharua] introduced the next step saying, there is a chance you will find what I’ll ask you to do now disagreeable, but this is an important part of the process.

Pointing to pellets of goat dung, he said, Go and fetch those. Once you gather them together, we will have to soak them in water. He handed me a clay bowl and said, this is a very important step. I did as I was told. Next, he pointed to a shil-nora and said, now you have to grind them up with the pestle. At that moment, my mother’s face fleetingly flashed before my eyes, but I did not allow it to weaken my resolve. After I finished grinding it, he ordered – A few different types of clay are kept over there. Sift them well. You need to mix a third of what you just ground with the clay carefully and then make a torso and a leg on the shil. I followed his instructions. [180]

But it is not just metal crafting processes and metal casting techniques that she writes about in this journal. Nothing escapes her keen observation: the relationships between men and women, both in the domestic and social sphere; their alcohol addiction; their games (some violent, others playful); the myths and deities that rule their life – especially Shitala and Danteshwari; and the famed Dussehra Durbar (at Jagdalpur) of Maharaja Pravir Singh Bhanj Deo of Bastar.

Finding herself

The most striking features of Meera Mukherjee’s life – as revealed in this book – are the lengths she went to, to find herself, and the perennial precarities she struggled with. No artist’s journey is ever easy. But hers was a particularly steep ascent to the peak of self-realization.

She was an arduous student who kept pushing herself into new frontiers of learning and practice, initially propelled by the exigencies of her personal life (an early marriage and divorce that took her a long to overcome), but later motivated by an inner compulsion of her own. Her initial training at the Indian Society of Oriental Art in the late 1930s was followed by five years at the Delhi Polytechnic (1947-51) and a brief apprenticeship under the Indonesian artist Affandi Koesoema in Santiniketan. Her major break however came when she secured a scholarship to study at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts (from 1952-56) and had the opportunity to train under Tony Stadler, a renowned German sculptor. After her return home, she would travel extensively to research the living traditions of metal craftsmanship – first at Bastar (1960), then at Bangalore (1961) with a stipend from the All India Handicrafts Board, followed by an apprenticeship under Prabhas Sen at the Regional Design Centre in Calcutta.

According to Guha-Thakurta, “It was her continuing impulse to keep travelling and learning from artisanal communities that made her pursue a new career trajectory of the artist-as-anthropologist”. The apotheosis of that was attained with an ASI Senior Fellowship (1962-1964), where she undertook “a comprehensive survey of practising [artisanal] communities” – which resulted in a seminal publication, Metalcraftsmen of India.

Mukherjee would channel all that learning into her practice as a sculptor. It would develop into an oeuvre with a signature style that, by the 1980s, found a steady clientele and was being periodically exhibited in galleries. But the process of her work entailed uncertainties at every phase and, most of it being un-commissioned, always remained financially strenuous. Settling into a seasonal cycle of sculpting helped combat the uncertainties somewhat; the major portion of the preparatory work of her sculpting - clay cores, wax models and outer casting – was done at her Calcutta residence in Paddapukur, from spring to monsoon, while casting and breaking of crucibles were carried out in winter in her studio at Elachigram. Learning music sustained her spiritually; but her life and work were fundamentally grounded in her companionship with and the unstinting support she received from Nirmal Sengupta – a profound bond that deified labels.

Building community

Mukherjee’s fierce commitment to self-actualization as an artist was accompanied by an equally robust belief in building/supporting artistic communities. It is best exemplified in the ‘Kantha Project’ hers with the children and women of Nalgorhat village (on the outskirts of Calcutta) that led to an Exhibition at Seagull Art Gallery in 1982, “The Stitchpainters of Dhankhet Vidyalaya”. But its most sustained manifestation was the group of artisans and assistants who helped shape her creations at the two venues of her work – Paddapukur and Elachigram. It was these trusted lieutenants who completed her last masterpiece, the Buddha, after her sudden death in 1998 – from raising funds to bringing together the 66 parts of the giant sculpture and then transporting it to its remote hilltop destination of the Badamtam Tea Estate in Darjeeling, owned by the Goodricke group.

This book can be taken as an example of the same ethic of collective labour, which will grant access to Meera Mukherjee’s life and work to a wide audience.

-

-

-

-

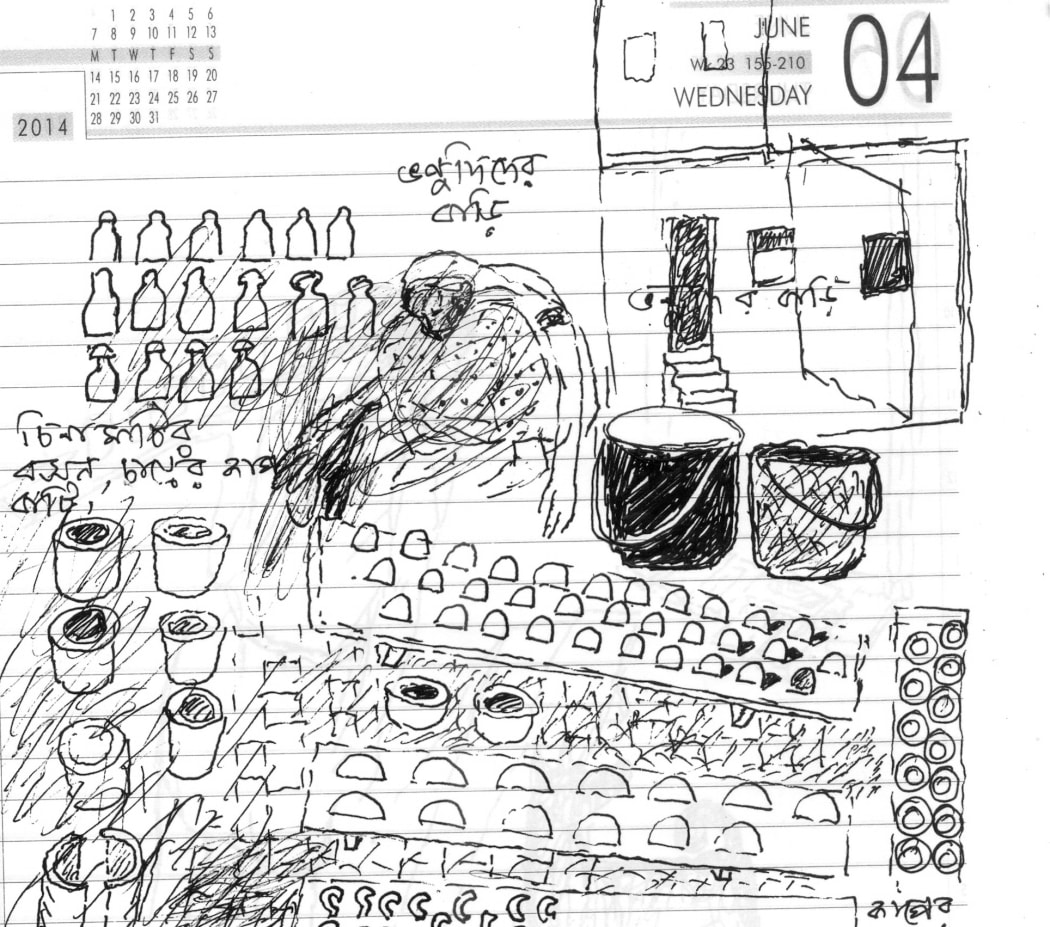

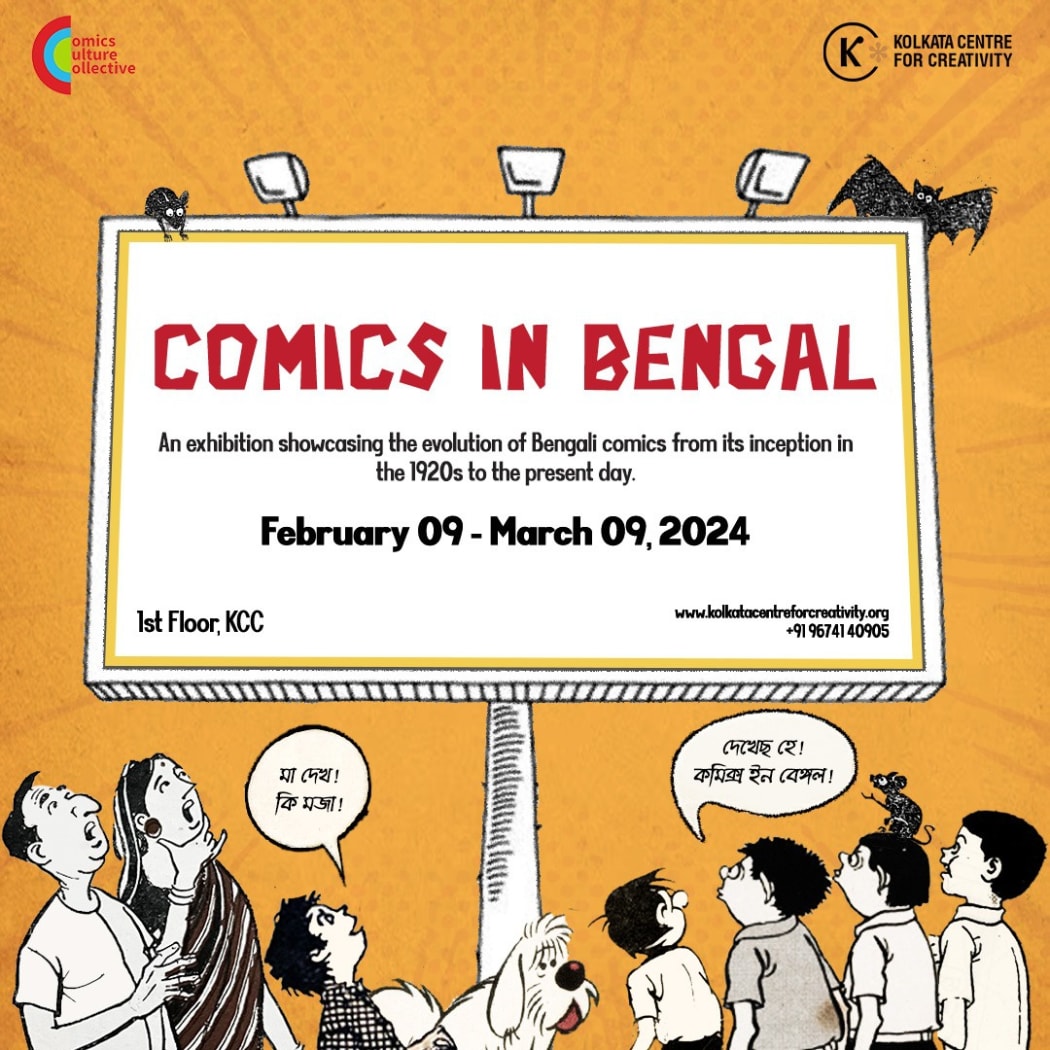

The Charm of Picture Books: Showcasing Bengali Comics in a New Light

by Shrutideep Majumder -

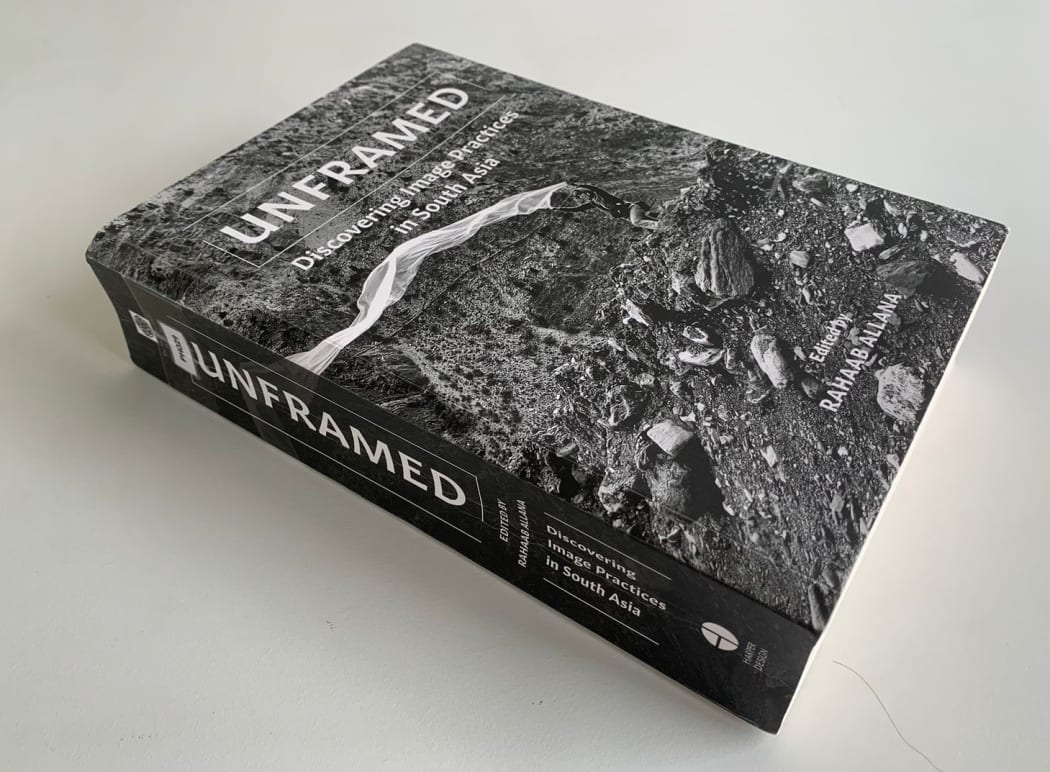

Unframed: Discovering Image Practices in South Asia, Harper Design, 2023 Courtesy: Emami Art

Unframed: Discovering Image Practices in South Asia, Harper Design, 2023 Courtesy: Emami ArtUNFRAMED: Opening Up New Horizons in the Study of Image Practices in South Asia

by Srilagna Majumdar -

-

-

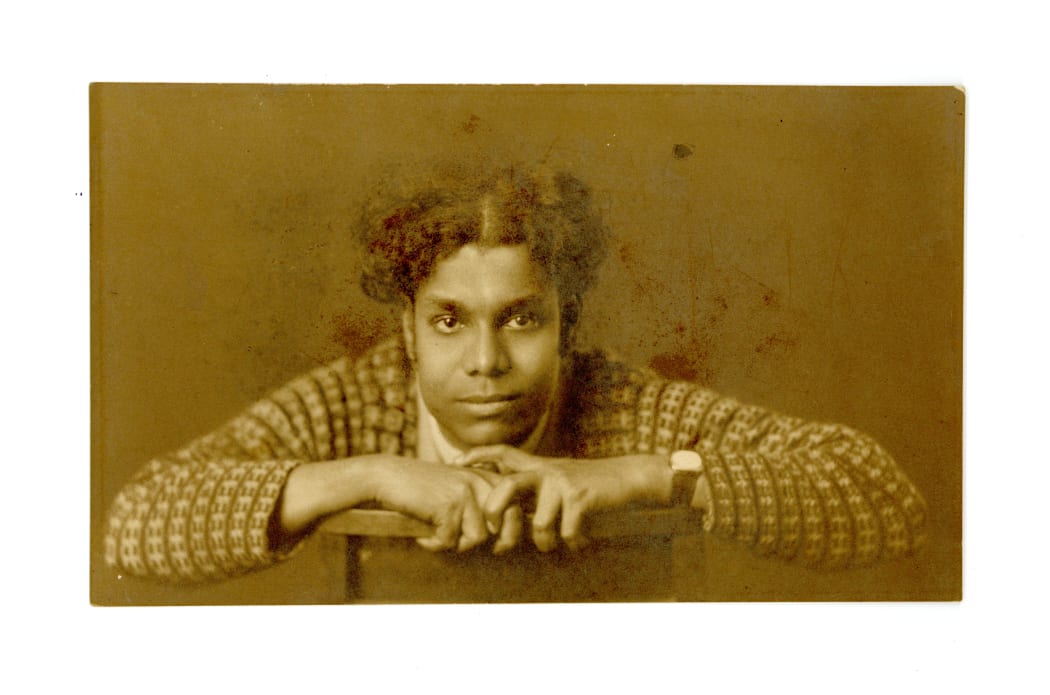

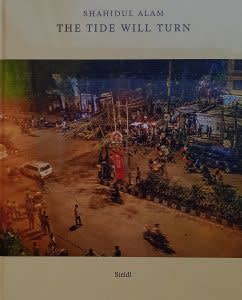

In a Cannibal Time: Photographs by Naveen Kishore, Emami Art, Kolkata

In a Cannibal Time: Photographs by Naveen Kishore, Emami Art, Kolkata -

-

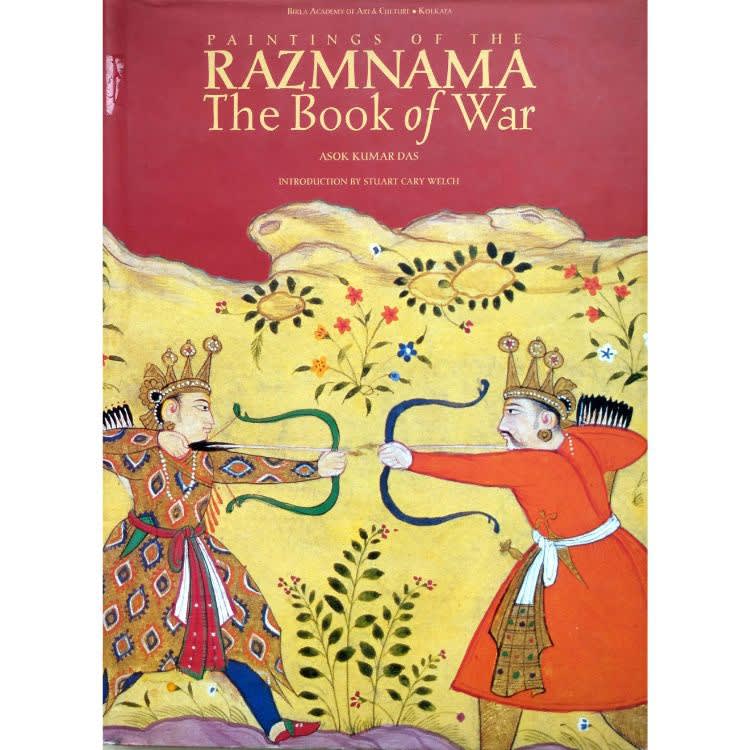

Paintings of the Razmnama, Asok Kumar Das, Mapin Publishing

Paintings of the Razmnama, Asok Kumar Das, Mapin Publishing -

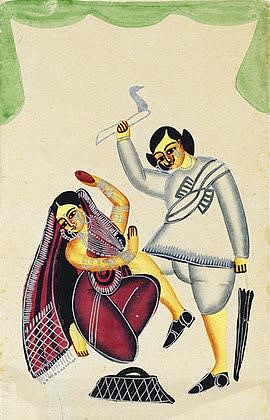

Scene of Nabin killing Elokeshi | Watercolour on paper | PikspostThe Kalighat Patuas, named so since they mainly settled in and around the Kalighat and Tarakeshwar Temples in Calcutta, migrated from various parts of Bengal, especially regions of Birbhum, Murshidabad, and Medinipur, the erstwhile royal centres. History shows that no cultural or intellectual output can exist in a vacuum.

Scene of Nabin killing Elokeshi | Watercolour on paper | PikspostThe Kalighat Patuas, named so since they mainly settled in and around the Kalighat and Tarakeshwar Temples in Calcutta, migrated from various parts of Bengal, especially regions of Birbhum, Murshidabad, and Medinipur, the erstwhile royal centres. History shows that no cultural or intellectual output can exist in a vacuum. -

-

After completing his graduation course from Presidency College, Satyajit Ray joined Kala Bhavan when he was only twenty years old. His mother, Suprabha Ray, wife of late Sukumar Ray, did not allow him to enter a job at this early age. Moreover, the poet Rabindranath Tagore wanted the son of Sukumar Ray as a student of his Visva-Bharati Santiniketan school. When Sukumar Ray died of Kala-azar, Satyajit was barely two years old, and it was not possible to send him to a boarding school. Suprabha Debi would not part with her son when he was just a school-going boy. She brought him up single-handedly.

Suprabha Debi thought that they should respect the poet’s wish to get Sukumar’s son as one of the students of his school. Satyajit himself was also convinced to take up a course on fine arts in Kala Bhavan under the tutelage of Nandalal Bose. He was deeply interested in book illustration, just like his father. His grandfather Upendra Kishore Ray Chowdhury was also a great book illustrator and an accomplished artist. So painting and book illustration was in Satyajit’s gene.

-

In the Mahabharata, the prince Arjuna holds ten names. Of those, one is Partha. Sarathi is a Sanskrit word meaning charioteer. In the battle of Kurukshetra, Sri Krishna, the king of Dwarka, decides not to take part as a warrior but as the charioteer of Arjuna. Therefore Parthasarathi means Sri Krishna, the charioteer of Arjuna.

At the outset of the Kurukshetra battle, Arjuna requests Sri Krishna to drive his chariot at the middle of the battleground to see both the Kaurava and Pandava armies from an equal distance. As his chariot reaches the centre, Arjuna sees all the warriors from both sides are his relatives and gets disheartened thinking of the devastating consequence of the war. He gets perplexed and decides to quit. At this moment, Sri Krishna motivates and persuades him to fight using his words and panentheistic divine image. Sri Krishna and Arjuna had a long conversation, compiled in the sacred book called Srimadbhagabad Gita. Executed in 1912, this watercolour painting, the subject matter of this essay, is an imaginative still taken from that conversation.

-

Nani Gopal Ghosh (1930-2014) , more popularly known as Nanida in Santiniketan, had a dramatic backdrop in his life to carry with him before he came to Santiniketan. It is important to know his story to understand him as a person, an artist and an Ashramik or inmate of the Santiniketan campus. He came to Santiniketan and joined Kala Bhavana, as a student, in May 1946 from Shibpur village in Noakhali, Bangladesh, via Chandpur and Gwalondo steamer ghat. That was before India got Independence. In October of the same year, when the Puja vacations started, Nani Gopal was eager to go home and join in the festivities with his family. Nandalal Bose, Principal of Kala Bhavana at that time, forbade him to do so as news about riots of Noakhali had already started trickling into Santiniketan. Young Nani was distraught. He was so keen to go to his village that he disobeyed the Principal's suggestion and went ahead with his plans only to be caught in a wild vortex of gruesome communal hatred dominating his native place. He saw torture, assassinations, illegal detention, the war cry of communal hatred, injustice and disrespect from proximity. In a single night, his home of a vast joint family was burnt down. Members died and escaped –he did not have full knowledge. He, too, ran with the help of some Muslim friends to Tripura. In Tripura, within some time, his big joint family separated into fragments. Motherless Nani Gopal did not find a place in his father and stepmother's family, nor for that matter, in any other family branch. He was caught amid the recent terrible memory of the riots behind and an uncertain shelterless future ahead.

Nani Gopal Ghosh (1930-2014) , more popularly known as Nanida in Santiniketan, had a dramatic backdrop in his life to carry with him before he came to Santiniketan. It is important to know his story to understand him as a person, an artist and an Ashramik or inmate of the Santiniketan campus. He came to Santiniketan and joined Kala Bhavana, as a student, in May 1946 from Shibpur village in Noakhali, Bangladesh, via Chandpur and Gwalondo steamer ghat. That was before India got Independence. In October of the same year, when the Puja vacations started, Nani Gopal was eager to go home and join in the festivities with his family. Nandalal Bose, Principal of Kala Bhavana at that time, forbade him to do so as news about riots of Noakhali had already started trickling into Santiniketan. Young Nani was distraught. He was so keen to go to his village that he disobeyed the Principal's suggestion and went ahead with his plans only to be caught in a wild vortex of gruesome communal hatred dominating his native place. He saw torture, assassinations, illegal detention, the war cry of communal hatred, injustice and disrespect from proximity. In a single night, his home of a vast joint family was burnt down. Members died and escaped –he did not have full knowledge. He, too, ran with the help of some Muslim friends to Tripura. In Tripura, within some time, his big joint family separated into fragments. Motherless Nani Gopal did not find a place in his father and stepmother's family, nor for that matter, in any other family branch. He was caught amid the recent terrible memory of the riots behind and an uncertain shelterless future ahead. -

Somnath Hore’s Vietnamese Mother

R Siva KumarSomnath Hore is known as an artist with a singular focus on human suffering. He saw suffering not as an ontological fact of existence, but as the outcome of an unjust social system we have built and continue to perpetuate. This meant that it could be changed, and to him, the solution lay in socialist political action. Early in his life, he joined the Communist Party to be a part of this process. But while trying to do this he soon realized two things. One, art guided by the Party can degenerate into propaganda and the production of art can be reduced into an unthinking mechanical process. Two, that to keep emotions alive and intense, and the message fresh, one had to innovate. In art, he realized, one had to change even to remain the same. So he adopted, mastered and extended available mediums, and developed new ones. The white on white prints made by pouring paper pulp into matrixes prepared from moulds made from clay or wax surfaces, and the singular sculptures made by cutting, joining, and hand modelling of thin wax sheets, and then made permanent by casting using the lost wax process were two of his last and more personal innovations.

-

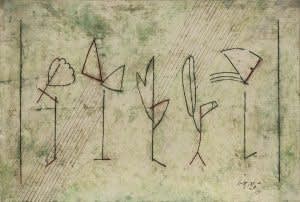

Ganesh Haloi is one of the most celebrated names in the Indian art scenario, who is sought-after for his non-representational abstract images. His stylistic individuality is undeniably unique in its formal appearance and technical efficacy. Although scholars and critics have acknowledged his paintings as the harmony of senses and sensibilities,1 ensemble of ‘pictorial signs’, ‘evocative marks’,2 and ‘quantum of colour’ 3 (Image 1); they are nevertheless interpretations based on, to paraphrase Edmund B. Feldman (1987, p. 474), the ‘formal analysis’ 4 of Haloi’s paintings. They examine the organisation of different visual elements – such as lines, shapes, colours, and textures – as forms in relation to their particular locations on the pictorial surface. These visual organisations are then perceived through the lens of their personal experiences, gathered from different sources. But certainly, there could be another or a different kind of explanation for his paintings – something that is akin to Haloi’s personal experiences, and not of the critics.

-

"With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people's lives, creating expectations, making friends – all these emotional entanglements come upon the disengagement that follows. Photographers, like myself, deal with people. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away?"

"With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people's lives, creating expectations, making friends – all these emotional entanglements come upon the disengagement that follows. Photographers, like myself, deal with people. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away?" -

Why contemporary art carpets you ask?

Carpets and Rugs! The use of these words brings forth the imagery of a beautiful tradition. I was pursuing my studies as a textile designer, I always wanted to transcend my painting into something more than the frame of my canvas. That is when I came across carpets being used by artists not only in India but globally as a gateway for the free flow of ideas and visualization.

-

Batik originates from the Javanese word Ambatik (Amba which means to write, and Titik, which means dots). An ancient wax-resist dyeing tradition with highly sophisticated artistic skills, which involves creating patterns and designs on fabric using molten wax and different dyes, Batik developed in Indonesia and the island of Java. Although the place of origin of Batik is still debated, the evidence of some wax-resist dyed fabric has been widely found at various times over the last two millenniums in Indonesia, Japan, Egypt, Malaysia and India. In India, Santiniketan in West Bengal, Mundra in Gujrat, Indore in Madhya Pradesh and Injambakkam in Tamil Nadu are the significant places where Batik is still being practised.

Batik originates from the Javanese word Ambatik (Amba which means to write, and Titik, which means dots). An ancient wax-resist dyeing tradition with highly sophisticated artistic skills, which involves creating patterns and designs on fabric using molten wax and different dyes, Batik developed in Indonesia and the island of Java. Although the place of origin of Batik is still debated, the evidence of some wax-resist dyed fabric has been widely found at various times over the last two millenniums in Indonesia, Japan, Egypt, Malaysia and India. In India, Santiniketan in West Bengal, Mundra in Gujrat, Indore in Madhya Pradesh and Injambakkam in Tamil Nadu are the significant places where Batik is still being practised. -

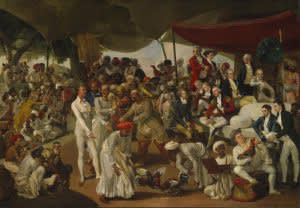

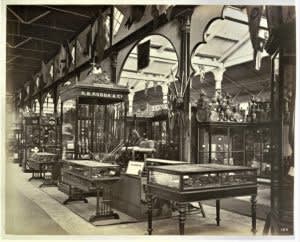

The first essay in this series (https://www.emamiart.com/blog/mapping-the-field-of-exhibition-history-the-calcutta-international-exhibition-of-1883-84/) discussed the workings of ‘world exhibition’ culture that was introduced in Calcutta, through the Calcutta International Exhibition in 1883-84. This exhibition remains to be the first and the last exhibition of a monumental international scale of the pre-independent India, as the exhibition format and its objectives which adhered largely to colonial thrusts of trade policies, didn’t find lasting grounds in Bengal. This failure was due to the rising animosity between the Indians and European population in Bengal stirred by the Ilbert Bill (1884) and also due to the lack of scholarly and commercial interest in the fair. However, the consequences of the large-scale circulation of art objects and artifacts during the exhibition made a significant impact on the colonial art education policy and on the rearrangement of object categories in the Indian Museum – a detailed account of which has been shared in the previous essay. As this series of episodic essays intend to raise some fundamental questions like – “How much have we negotiated with the classifications of material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices?” Through the trope of the exhibition as a facilitator, each blog post will trace and analyze the foundational methodologies of exhibition-making as a modernization process in the region; and the current second essay will look into the formation of the first public art gallery in Calcutta.

The first essay in this series (https://www.emamiart.com/blog/mapping-the-field-of-exhibition-history-the-calcutta-international-exhibition-of-1883-84/) discussed the workings of ‘world exhibition’ culture that was introduced in Calcutta, through the Calcutta International Exhibition in 1883-84. This exhibition remains to be the first and the last exhibition of a monumental international scale of the pre-independent India, as the exhibition format and its objectives which adhered largely to colonial thrusts of trade policies, didn’t find lasting grounds in Bengal. This failure was due to the rising animosity between the Indians and European population in Bengal stirred by the Ilbert Bill (1884) and also due to the lack of scholarly and commercial interest in the fair. However, the consequences of the large-scale circulation of art objects and artifacts during the exhibition made a significant impact on the colonial art education policy and on the rearrangement of object categories in the Indian Museum – a detailed account of which has been shared in the previous essay. As this series of episodic essays intend to raise some fundamental questions like – “How much have we negotiated with the classifications of material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices?” Through the trope of the exhibition as a facilitator, each blog post will trace and analyze the foundational methodologies of exhibition-making as a modernization process in the region; and the current second essay will look into the formation of the first public art gallery in Calcutta. -

Like the Shakespearian jester in the royal court, the art of cartooning has been a quintessential disruptor in the symposium of fine arts. However, the cartoon has created a parallel path outside mainstream art history with its simplistic tools of visual communication and courage to confront with humour. During the advance of print media and independent publishing, cartoons attracted a lot of artists and made an enthusiastic audience base due to their popular appeal. In the colonized Bengal, with the uprising of the independent presses, political cartooning emerged as a vital tool on the onslaught of a socio-cultural and political revolution. Starting from the caricatures published by Harbola Bhand and Basantak in the 1870s, the art form flourished through the journey of Bengali periodicals and newspaper editorials.

Like the Shakespearian jester in the royal court, the art of cartooning has been a quintessential disruptor in the symposium of fine arts. However, the cartoon has created a parallel path outside mainstream art history with its simplistic tools of visual communication and courage to confront with humour. During the advance of print media and independent publishing, cartoons attracted a lot of artists and made an enthusiastic audience base due to their popular appeal. In the colonized Bengal, with the uprising of the independent presses, political cartooning emerged as a vital tool on the onslaught of a socio-cultural and political revolution. Starting from the caricatures published by Harbola Bhand and Basantak in the 1870s, the art form flourished through the journey of Bengali periodicals and newspaper editorials. -

Art, across its ever-expanding spectrum of forms, sub-forms and inter-forms, steps into express the otherwise less readily expressible. It is not as though art merely provides for a lack or affords a surplus, and that art is that extra something that can be periodically accommodated or rejected at will. Rather, my opening proposition is an invitation to probe where art's necessity as a language lies. In certain cases, the very non-specific and otherwise inexpressible nature of the experience is what lends itself to its expressibility in art. In others, it is the art-form that creates or re-fashions a new experience or perception by dint of its intrinsic expressiveness. Where the latter happens, the alterity is bestowed by the form instead of being innate to the matter.

Art, across its ever-expanding spectrum of forms, sub-forms and inter-forms, steps into express the otherwise less readily expressible. It is not as though art merely provides for a lack or affords a surplus, and that art is that extra something that can be periodically accommodated or rejected at will. Rather, my opening proposition is an invitation to probe where art's necessity as a language lies. In certain cases, the very non-specific and otherwise inexpressible nature of the experience is what lends itself to its expressibility in art. In others, it is the art-form that creates or re-fashions a new experience or perception by dint of its intrinsic expressiveness. Where the latter happens, the alterity is bestowed by the form instead of being innate to the matter. -

Her confidently draped saree, motia (jasmine) adorned scanty bun, kind eyes behind the glasses and a warm and welcoming smile on her thin lips -- people who met her in her ripe old age has this humble image of her etched in their minds. Suraiya Hasan Bose (1928 –2021), a legendary textile revivalist, pioneering entrepreneur and advocate of women’s empowerment, fondly called ‘Suraiya apa’ by the community of weavers, textile connoisseurs, researchers, students and those who loved her and admired her for her enormous contribution to the field of textile. Her weaving unit and outlet, House of Kalamkari Durries in Hyderabad, was like the second home for many of us. With her demise in September and the untimely closure of the weaving unit in November 2019, a significant chapter of the textile revivalist movement in post-independent India has ended. It has remained treasured only in memories of the unnumbered people who had a chance to get associated with her. My essay attempts to revisit a brief history of the weaving unit, focusing on its final years that decayed in a parallel manner to Suraiya apa’s frail body and fading memories.

-

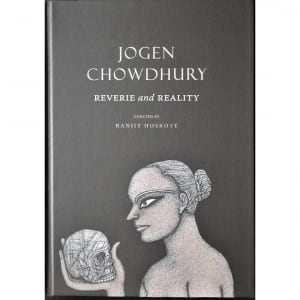

The exhibition books accompanying the carefully curated, retrospective-scale exhibitions of Dashrath Patel, Jogen Chowdhury and Kartick Chandra Pyne at Emami Art between 2018 and 2020 delve deep into the life and work of the three modern masters. Lavishly illustrated, the books, based on foundational research on the artists, offer a glimpse of the exhibitions, presenting the side of their practice, rarely seen and scarcely explored.

-

Paper may be precious, printing technologies transform, and production methods expand—but the potential of the book as a creative form will remain available for exploration

-Johana Drucker, The Century of Artists’ Book

-

Bishnu Prasad Rabha (1909-1969) or Bishnu Rabha is one of the pioneering, colossal figures of the socio-cultural phenomenon known as Assamese modernism in the early 20th century. He was an accomplished and fine artist, painter, playwright, litterateur, singer and dancer, and a great revolutionary. An extraordinary versatile genius, he, for his lifetime, remained a champion of Marxist ideologies and relentlessly fought for the rights of the oppressed and mending the dismantling social and cultural fabric of Assam in the 19th to 20th century. Along with other dominant figures of Assamese modernism and advocates of progressive thought like Jyotiprasad Agarwalla, he contributed immensely to shaping the Assam we know today.

Bishnu Prasad Rabha (1909-1969) or Bishnu Rabha is one of the pioneering, colossal figures of the socio-cultural phenomenon known as Assamese modernism in the early 20th century. He was an accomplished and fine artist, painter, playwright, litterateur, singer and dancer, and a great revolutionary. An extraordinary versatile genius, he, for his lifetime, remained a champion of Marxist ideologies and relentlessly fought for the rights of the oppressed and mending the dismantling social and cultural fabric of Assam in the 19th to 20th century. Along with other dominant figures of Assamese modernism and advocates of progressive thought like Jyotiprasad Agarwalla, he contributed immensely to shaping the Assam we know today. -

Discussions on curatorial projects, museum collections, classification and categorization of museum objects and institutional histories across the globe have gathered much public attention crossing the scope of academia through zoom webinars during this pandemic era. Scholastic repositories are gradually opening up, and research-driven methodologies are being imbibed more in artistic dialogues of our time, touching upon the range of data that scholars and historians once exclusively determined. In this scenario, I often find myself submerged in the ocean of historical data only to peep out to comprehend the cultural precipice being built on the disciplinary field of art practice and its history. How much have we negotiated with the classifications in a material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices? Sifting through these questions can also reveal the awkwardness in institutional conservatism that has been set in loop. There are no right or wrong conclusions to these inquests, but a historical trail can lead us to the beginning of the hallowed domain of making the ‘modern and contemporary art’ genre in India, which is vehemently addressed as institutional agendas. And the domain of ‘Exhibition Making’ in the country has been the prime vehicle of the genre.

Discussions on curatorial projects, museum collections, classification and categorization of museum objects and institutional histories across the globe have gathered much public attention crossing the scope of academia through zoom webinars during this pandemic era. Scholastic repositories are gradually opening up, and research-driven methodologies are being imbibed more in artistic dialogues of our time, touching upon the range of data that scholars and historians once exclusively determined. In this scenario, I often find myself submerged in the ocean of historical data only to peep out to comprehend the cultural precipice being built on the disciplinary field of art practice and its history. How much have we negotiated with the classifications in a material culture which India adopted during colonization? How have we adopted our understanding of display? What is the politics of white cube exclusivity? How does categorization/classification/disciplinary specialization remain to be relevant in the milieu of cross-disciplinary practices? Sifting through these questions can also reveal the awkwardness in institutional conservatism that has been set in loop. There are no right or wrong conclusions to these inquests, but a historical trail can lead us to the beginning of the hallowed domain of making the ‘modern and contemporary art’ genre in India, which is vehemently addressed as institutional agendas. And the domain of ‘Exhibition Making’ in the country has been the prime vehicle of the genre.